Early Life and Education

C.S. Lewis’s childhood in Belfast, Ireland, was as vivid and complex as the stories he later shared with the world. His early years were marked by a confluence of familial warmth, literary discovery, and formative challenges that would shape not only his intellect but also his deeply reflective view of life.

Birth and Family Background

Born on November 29, 1898, in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Clive Staples Lewis was raised in a family that valued education and intellectual curiosity. His father, Albert James Lewis, worked as a solicitor—a profession demanding both precision and a grasp of human nature. His mother, Florence Augusta Hamilton Lewis, was a rarity for her time: a university graduate from the Royal University of Ireland. It was from Florence that Lewis inherited a love of books and a keen intellectual rigor.

Lewis’s Protestant upbringing in Northern Ireland positioned him within a cultural milieu rich with tradition, yet fissured by sectarian divides. This dichotomy of security within his family and tension in the broader society likely influenced his later preoccupation with moral and philosophical dualities. Alongside his older brother, Warren (“Warnie”), Lewis experienced a household suffused with the sounds of debate, laughter, and the occasional pangs of loss—a recipe for a mind primed to wrestle with the complexities of human existence.

For more on Lewis’s family background, visit C.S. Lewis: A Profile of His Life.

Early Love for Literature

The Lewis household was practically a temple of books, where sprawling stories and ancient mythologies lived alongside modern prose. By the age of four, young Clive had already declared his preference for being called “Jack,” a name he adopted after the death of his beloved dog (a name he used for the rest of his life). Books became his refuge and his sanctuary. He devoured everything in sight, from ancient epics to the modern novels lining his parents’ shelves.

One particularly transformative moment came when his father introduced him to Beatrix Potter’s timeless tales. For young Lewis, tales of anthropomorphic animals sparked the kind of imaginative curiosity that would eventually inspire The Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis’s childhood notebooks reveal a world-builder even in his youth, filled with sketches of fantastical lands and storied characters. It was, in essence, a life marinated in narratives—both real and imagined—that would eventually pour forth into his own writing.

To explore Lewis’s early literary foundation further, check out About C.S. Lewis – Official Site.

Boarding School Experiences

If the home was Lewis’s sanctuary, school was its stark antithesis. At the tender age of nine, Lewis was sent to Wynyard School in England following his mother’s untimely death from cancer. The school, governed by a headmaster later declared insane, was a dungeon more than an institution. Lewis referred to it as “Belsen,” drawing a grim parallel that underscored its punitive atmosphere.

His subsequent years at Malvern College proved less harrowing, though still challenging. It was during this phase that Lewis wrestled with his Christian upbringing, eventually rejecting faith altogether—a stance he maintained until his late twenties. Yet, these experiences also introduced him to individuals who would inspire and shape his intellectual growth, such as his private tutor William T. Kirkpatrick, whom Lewis later immortalized as “The Great Knock.” Under Kirkpatrick’s mentorship, Lewis refined his skills of logical reasoning and debate, becoming the sharp thinker known worldwide today.

For more on Lewis’s varied and tumultuous school years, visit The Life of C.S. Lewis Timeline.

In these early chapters of his story, we see the scaffolding of Lewis’s later life take shape—a blend of personal adversity, intellectual awakening, and creative blossoming.

Academic and Professional Life

The academic and professional trajectory of C.S. Lewis is the story of ambition meeting genius, resulting in a legacy that enriched not only universities but also the entire field of literature. From grappling with the harrowing experiences of war to later teaching at prestigious institutions, Lewis wove the threads of his life into an intricate tapestry of thought, reflection, and creation.

World War I and Its Impact

Photo by Keira Burton

Few experiences shape a person as profoundly as war, and World War I left its indelible mark on Lewis. Enlisting in 1917 as a young officer in the British Army, he was thrust into the horrors of trench warfare on the Western Front. While Lewis outwardly downplayed the war’s personal impact, its shadows are unmistakably cast over his works. His depiction of good and evil, often monumental in scale and human in consequence, owes much to the stark realities of that period.

War filled his worldview with a grim realism, yet also with a defiant hope. Later writings, such as The Screwtape Letters, mirror the moral weight and narrative tensions he found during his time in the battlefield. His camaraderie with fellow soldiers echoed in his fictional characters’ rich interpersonal dynamics. To explore more on this connection, you can visit C.S. Lewis and the Great War.

Teaching Career and Academic Achievements

In the halls of Oxford’s Magdalen College, Lewis’s erudition found its ideal setting. Appointed as a Fellow and Tutor in English Literature in 1925, he taught for nearly three decades, influencing countless students with his eloquence and encyclopedic knowledge. His lectures on Medieval and Renaissance English literature drew packed audiences, as much for his scholarship as for his magnetic delivery.

In 1954, Lewis transitioned to Cambridge, where he became the inaugural Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature—a role created specifically for him. His landmark works, including The Allegory of Love, remain cornerstones in the study of allegorical literature. It was here that his ability to bridge the medieval and modern found full expression, marking his contributions as timeless. Read more about his academic influence at About C.S. Lewis – Official Site.

Membership in the Inklings

No discussion of C.S. Lewis’s professional life is complete without mentioning the Inklings, an informal literary circle whose influence extends far beyond their Oxford gatherings. Formed in the 1930s, this group of thinkers and storytellers included such luminaries as J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, and Owen Barfield. They met regularly to share and critique each other’s writings, fostering an environment of rigorous creative exchange.

Lewis’s friendship with Tolkien, in particular, proved transformative. Though the two had ideological disagreements—Tolkien famously criticized Lewis’s liberal use of allegory in The Chronicles of Narnia—their mutual respect and camaraderie were deeply rooted. Tolkien’s influence is evident in Lewis’s return to Christianity, while elements of Lewis’s imaginative style can be traced in Tolkien’s fantastical world-building. To dive deeper into their dynamic, visit C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and the Inklings.

Whether in the trenches of war, the lecture halls of Oxford, or the convivial gatherings of the Inklings, every chapter of Lewis’s professional life added another layer to his complex and enduring legacy.

Spiritual Journey and Christian Apologetics

No discussion about the life of C.S. Lewis would be complete without examining the profound transformation and intellectual rigor that characterized his spiritual journey. His evolution from staunch atheism to fervent Christianity is not just a testament to his intellectual sincerity but also the foundation of his later works as one of the most significant Christian apologists of the 20th century.

Journey from Atheism to Christianity

Lewis’s early years were defined by a rejection of faith, rooted in both personal suffering and intellectual challenges to theism. Raised in a Protestant household, he experienced a profound spiritual disillusionment following his mother’s untimely death. The logical reasoning he honed under William T. Kirkpatrick, his private tutor, further reinforced his atheistic outlook. As Lewis later reflected, he embraced atheism “not out of joy or defiance, but as a type of liberation from the constraints of faith.”

Still, life has a curious way of weaving irony into its narrative. At Oxford, Lewis began to encounter thinkers who challenged his disbelief—figures like Owen Barfield and J.R.R. Tolkien. It was Tolkien who, like a gentle but persistent craftsman, chipped away at the foundations of Lewis’s atheism. Their debates on myth and meaning culminated in a shared walk along Addison’s Walk in 1931, where Tolkien argued that Christianity served as the ultimate “true myth,” combining historical reality with profound spiritual truth.

Through these discussions and an intense personal reckoning, Lewis found himself reluctantly but irresistibly drawn to faith. In his autobiography Surprised by Joy, Lewis described himself as “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.” Yet what began as intellectual ascent quickly unfolded into a deeply personal belief in Christ—a transformation that laid the groundwork for his monumental contributions to Christian thought. Those interested in Lewis’s dramatic spiritual arc can explore more in The Conversion Story of C.S. Lewis.

Major Christian Apologetic Works

Lewis’s newfound faith ignited a prolific phase of writing, tackling the great questions of life, morality, and theology with vigor. His apologetic works were not just attempts to advocate for Christianity but also intellectual explorations of what he considered timeless truths.

- Mere Christianity: Born from a series of BBC radio talks, this book remains one of his most celebrated works. Lewis distilled the core beliefs of Christianity into lucid and relatable arguments, offering readers both clarity and conviction. His analogy of Christianity as a “house”—with various rooms representing denominations—still resonates as a vision of unity amidst diversity. For insights into this work, see A Guide to the Major Works of C.S. Lewis.

- The Screwtape Letters: Here, Lewis’s wit shines as he narrates the correspondence between a senior demon, Screwtape, and his apprentice nephew, Wormwood. The book serves as a satirical yet shrewd examination of human nature and the subtle spiritual forces at play. Through its paradoxical charm, Lewis manages to illuminate the tricks of temptation while pointing toward the redemptive power of grace.

- Surprised by Joy: This, perhaps his most personal work, chronicles Lewis’s journey from childhood grief and atheism to spiritual awakening. It’s less an academic treatise and more a poignant reflection on the moments of “joy” that led him toward faith.

Lewis’s work continues to inspire theologians and seekers alike, bridging the gap between intellectual rigor and heartfelt faith. His contributions to apologetics spark conversations that endure to this day.

Radio Broadcasts during World War II

Photo by Rajitha Fernando

During the uncertainty of World War II, Lewis took to the airwaves in a series of radio broadcasts for the BBC. These talks offered a voice of calm amidst chaos, addressing the moral and spiritual questions raised by the global conflict. At a time when despair threatened to engulf Europe, Lewis used these 15-minute segments to articulate the rational and redemptive nature of the Christian faith.

The broadcasts were later compiled into Mere Christianity, cementing their legacy. But beyond their theological content, the talks were also deeply pastoral. Lewis understood the weight of war, having been a soldier himself, and he spoke to his audience not as a detached intellectual but as a fellow traveler grappling with suffering and hope.

The broadcasts were striking in their accessibility. Whether discussing the meaning of morality, the nature of God, or the essence of human purpose, Lewis’s words resonated beyond theology professors to reach factory workers, soldiers, and homemakers. Their enduring power can be explored further in C.S. Lewis at the BBC: Messages of Hope.

Together, these writings and broadcasts underscore Lewis’s commitment to a faith he found not just plausible, but transformative. His journey reminds us that belief is rarely simple, yet profound truths often emerge through the most unlikely of paths.

Literary Contributions

Few authors have left a literary legacy as vast and varied as C.S. Lewis. From captivating children with magical adventures to challenging adults with deep theological discourse, Lewis managed to weave profound truths into stories that resonate across ages and cultures. His body of work reflects a mind steeped in imagination, philosophy, and a relentless quest for understanding human existence in light of the divine.

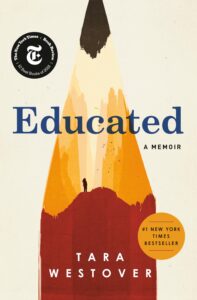

The Chronicles of Narnia

Photo by Pixabay

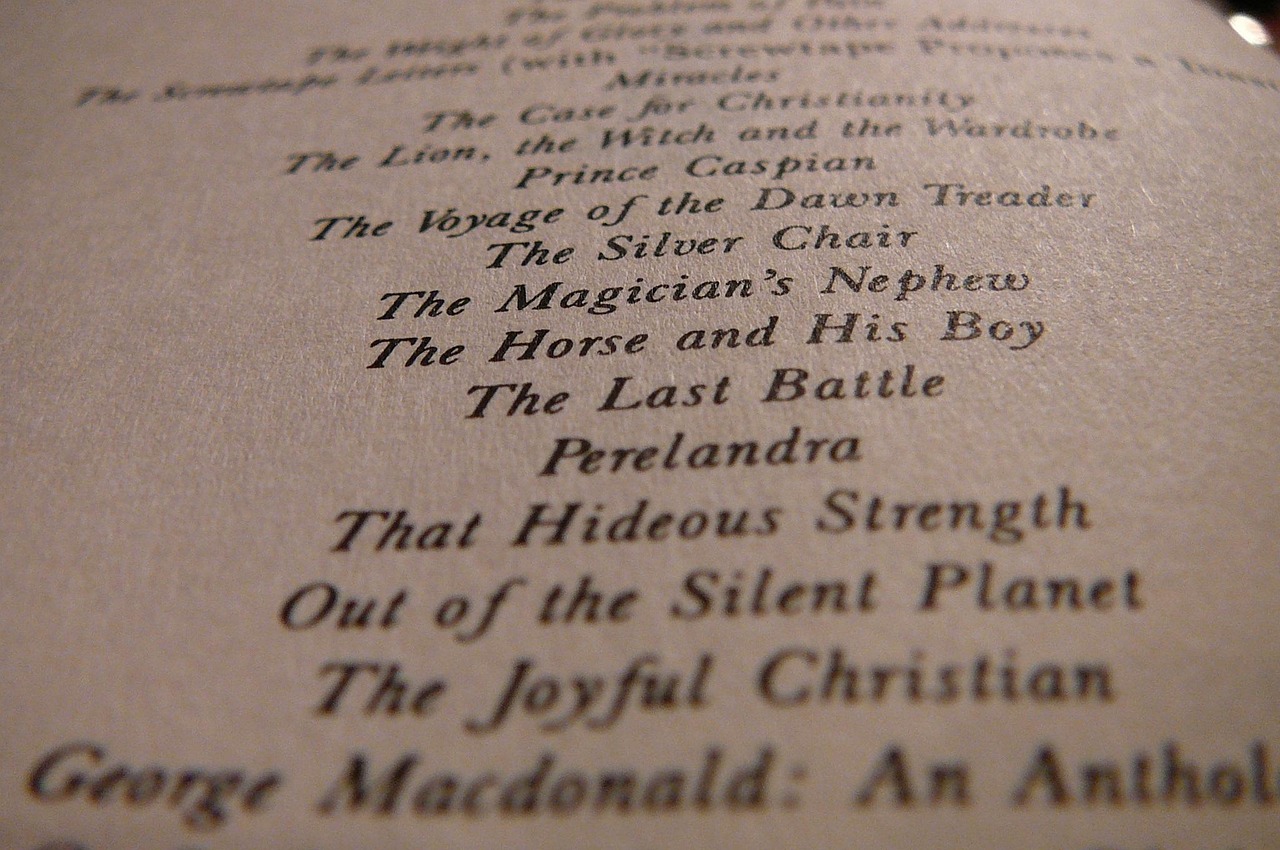

Arguably Lewis’s most celebrated work, The Chronicles of Narnia is a cornerstone of children’s literature. Published between 1950 and 1956, the series spans seven books, each filled with compelling characters, vivid settings, and an unmistakable sense of wonder. Lewis crafted Narnia as a place where mythical creatures, epic battles, and moral dilemmas converged, leading readers on a journey that was as entertaining as it was thought-provoking.

At its heart, Narnia is more than just a fantastical world; it is a stage for exploring universal themes of good versus evil, redemption, and sacrificial love. The character of Aslan, the noble lion, embodies these themes with unmistakable Christian allegory. Aslan’s willing death to save others—followed by his triumphant resurrection—mirrors the gospel narrative, yet never in a way that feels heavy-handed or inaccessible. Lewis believed that great stories could reveal profound truths indirectly, allowing readers to absorb ideas in a more emotional and experiential way.

The series’ impact has been staggering. Millions of copies have been sold worldwide, and the books continue to capture the imaginations of new generations. Adaptations in various forms—movies, television, plays—further attest to its enduring appeal. For a deeper look into the success and themes of Narnia, visit The Success of C.S. Lewis in The Chronicles of Narnia or explore The Main Themes of Chronicles of Narnia.

The Space Trilogy

In The Space Trilogy, Lewis ventured into the relatively uncharted waters of science fiction with an entirely unique approach. Comprising Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943), and That Hideous Strength (1945), the series eschewed pulp-style space adventures for an exploration of profound philosophical and theological questions.

Here, Lewis painted a cosmos filled with spiritual realities, where human sin and divine grace play out on a grand cosmic stage. For instance, Perelandra serves as Lewis’s “alternate Eden,” delving into the idea of temptation and potential redemption in a world untouched by original sin. Each book challenges readers to think beyond the material and to consider humanity’s place in a spiritually charged universe.

The trilogy combines elements of European mythology, Christian theology, and utopian science fiction, creating a genre-defying work that feels timelessly relevant. It also reflects Lewis’s profound understanding of moral struggle, reminding readers that the battle between good and evil is as much internal as it is external. To explore this underappreciated series in greater detail, see Why We Need C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy or Lewis: Space Trilogy | All Manner of Thing.

Essays and Other Non-Fiction

Beyond fiction, Lewis’s essays and non-fiction works reveal the depth of his intellect and his skill as a communicator. His essays, in particular, showcase his ability to tackle complex ideas with clarity and wit, covering topics as varied as literature, morality, and the human condition itself.

Collections such as God in the Dock and The Weight of Glory distill Lewis’s thoughts on faith and the modern world, often confronting the skepticism of his era head-on. His writing exhibits a rare combination of rigorous logic and imaginative eloquence, offering insights that remain strikingly relevant.

In his non-fiction, Lewis also explored the intersection of storytelling and truth. He believed that myths—and indeed, all great literature—could serve as vehicles for universal truths, transcending time and culture. This conviction is evident in both his essays and works like Reflections on the Psalms, where he examined how ancient scripture continues to speak to contemporary hearts and minds.

For those seeking a comprehensive guide to his essays and non-fiction works, the article How to Read All of C.S. Lewis’ Essays serves as a useful resource. Additional insights into his literary legacy can also be found in C.S. Lewis Novels and Nonfiction.

Through his essays, science fiction, and the unfading allure of Narnia, Lewis accomplished what few writers ever can: he spoke to both the heart and the mind, creating works that continue to challenge, inspire, and captivate.

Personal Life and Relationships

While C.S. Lewis’s literary and academic contributions often take center stage, his personal connections reveal much about the man behind the words. These relationships, profound and sometimes tragic, deeply influenced his worldview and writings.

Marriage to Joy Davidman

C.S. Lewis’s relationship with Joy Davidman was anything but conventional, yet it was perhaps one of the most poignant chapters of his life. Davidman, an American poet and writer, first connected with Lewis through correspondence. Their intellectual exchange quickly blossomed into a deep friendship that eventually led to love. Despite their vastly different backgrounds, the pair shared an uncommon understanding of faith, literature, and life’s enduring questions.

When they married in 1956, Joy was already battling advanced cancer. This somber reality would have likely deterred many, but for Lewis, it was a deliberate act of devotion. He famously wed her in a civil ceremony in the hospital, knowing full well their time together would be heartbreakingly brief.

Their love story, though marked by suffering, left an indelible impression on Lewis’s writing. After Joy’s death in 1960, he penned A Grief Observed under the pseudonym N.W. Clerk. This raw, unvarnished account of his heartbreak is a poetic meditation on the nature of grief, faith, and the human condition. The work transcends personal pain, resonating universally with anyone who has experienced loss. It captures both the hollowness of her absence and the tender hope that grief can lead to spiritual transformation. Explore more about this touching memoir at A Grief Observed.

Lewis’s own words remind us of the profound paradox of love: its ability to both wound and heal. In Joy, he found a kindred spirit whose brief presence in his life became the fulcrum for some of his most reflective and honest work. For a more personal look at their bond, see How Joy Davidman Altered My View of C.S. Lewis.

Friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien

Navigating the literary world of mid-20th-century England without encountering J.R.R. Tolkien would have been nearly impossible for Lewis, but their meeting was anything but accidental. Introduced at Oxford in the 1920s, these two titanic figures of literature quickly connected over their shared love of mythology, storytelling, and faith. What began as casual camaraderie deepened into a friendship that would leave a lasting mark on both men and their works.

Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, played a crucial role in Lewis’s reawakening to Christianity. The two often spent long hours in heated yet friendly debates, wrestling with questions of belief and the interplay between myth and truth. Tolkien argued that Christianity was the ultimate “true myth,” combining the imaginative beauty of storytelling with the concrete reality of historical events—a perspective that profoundly influenced Lewis’s eventual conversion.

Their literary collaboration was just as impactful. The pair belonged to the Inklings, a group of writers who critiqued each other’s works. Tolkien gave early feedback on The Chronicles of Narnia, while Lewis supported and admired Tolkien’s creation of The Lord of the Rings. Despite differences in literary approach—Tolkien disliked Lewis’s allegorical style—their connection thrived on mutual respect and shared intellectual pursuits.

However, the friendship was not without its strains. Over time, divergent theological views and professional jealousies created some distance between the two. Yet, Tolkien would later speak warmly of Lewis, describing him as “his closest friend for many years.” To dive deeper into their bond and its complexities, visit The Friendship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

Much like the rich worlds they created, the friendship between Lewis and Tolkien was layered, dynamic, and memorable. Their journeys, both individual and shared, remind us that even the greatest minds benefit from the sharpening influence of a kindred spirit. As fellow creators of myth and meaning, they exemplified the power of friendship to inspire and challenge, forging ideas that continue to captivate readers today.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

C.S. Lewis’s enduring influence stretches far beyond his lifetime, leaving an indelible mark on modern Christian thought and the world of literature and media. His works continue to resonate, offering clarity and depth in theological discourse while inspiring countless adaptations in storytelling.

Impact on Modern Christian Thought

Photo by Mike Bird

C.S. Lewis occupies a unique space in the discussion of Christian theology, serving as both an intellectual guide and a spiritual mentor for millions. His ability to simplify complex theological concepts without distorting their essence transformed him into a bridge between academic discourse and lay understanding. Works like Mere Christianity dismantled barriers to faith, framing Christianity not as an esoteric doctrine but as a practical, universal truth. It was this accessibility, paired with a razor-sharp intellect, that cemented Lewis as one of the great apologists of the 20th century.

Lewis’s remarkable depth of insight continues to shape contemporary Christian thought. His analogy of the faith as a house, with various denominational “rooms,” still inspires ecumenical dialogue. The clarity with which he juxtaposed faith and reason has encouraged countless skeptics to reconsider spiritual perspectives. This lasting relevance is evidenced by modern theologians and thinkers who routinely cite his work. For more on his theological contributions, visit C.S. Lewis’s Effect on Modern Christianity.

Modern culture frequently revisits Lewis’s apologetic methods, drawing from his ability to present timeless truths with vivid imagery and relatable metaphors. His influence has permeated sermons, academic courses, and even discussions within secular circles that seek to understand religion’s impact on ethics and meaning. If Lewis was an evangelist, he was one without a pulpit, using his pen to echo the eternal themes of hope and redemption.

Influence on Literature and Media

From the silver screen to academic syllabi, C.S. Lewis’s literary influence is everywhere. Best known for The Chronicles of Narnia, Lewis created stories that offer a perfect blend of entertainment and moral profundity. While the adventures of Aslan and his companions have thrilled children, their allegorical depth continues to engage adults. These works are a masterclass in embedding truths within seemingly simple narratives, ensuring their timelessness.

The adaptations of Narnia, ranging from blockbuster films to stage productions, stand as a testament to their enduring appeal. These reimaginations have introduced Lewis’s magical world to new generations, proving the relevance of themes like courage, sacrifice, and reconciliation. Beyond Narnia, Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters and The Space Trilogy have also inspired creative endeavors in theatrical adaptations and literary analyses. For a discussion on his literary contributions’ lasting significance, see Why C.S. Lewis Is as Influential as Ever.

Lewis’s influence is not restricted to his literary universe; his essays on storytelling and imagination have shaped how we understand the art of writing itself. He championed the idea that stories are not mere escapism but a means to illuminate profound truths. When watching a modern fantasy epic or reading any tale with allegorical undertones, one might detect a whisper of Lewis’s methodology and philosophy.

Through his works, Lewis taught that stories have the power to transform, to comfort, and to guide. His legacy in media and literature serves as a reminder of the enduring importance of narrative in shaping how we see the world—not just as it is, but as it could be.

Conclusion

C.S. Lewis’s life and work remain a testament to the power of faith and imagination interwoven with intellectual pursuit. His ability to craft narratives that engage both the heart and mind has secured his place as one of the most influential thinkers and storytellers of the modern era.

From the enduring magic of The Chronicles of Narnia to the rational eloquence of Mere Christianity, Lewis transcended genre and audience, leaving a legacy that bridges literature, theology, and philosophy. He transformed his personal struggles and profound introspections into works that challenge and uplift readers across generations.

If you’ve yet to explore his writings, now is as good a time as any to let Lewis guide you into the deeper questions of life, belief, and wonder. What might you discover when you step through the wardrobe of his ideas?