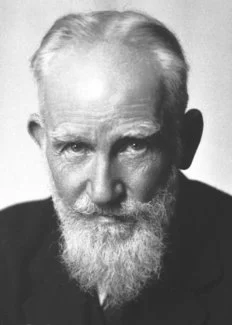

George Bernard Shaw’s name stands as a towering figure in the world of literature, resonating with a sharp intellect and an unyielding commitment to challenging convention. As the recipient of both a Nobel Prize in Literature and an Academy Award, Shaw carved a niche that transcended the boundaries of traditional theater. His works, such as Pygmalion, Saint Joan, and Man and Superman, are more than just plays—they’re explorations of human behavior, society, and the moral dilemmas that shape our existence. Through the wit and wisdom of his writing, Shaw didn’t just entertain; he educated, provoked, and redefined what it meant to create meaningful art.

Shaw’s legacy, richly layered in themes of equality, faith, and human ambition, continues to inspire generations. His stories remain as relevant now as when they were first staged—timely critiques of society wrapped in eloquence and humor. If you’ve ever wondered why Shaw’s work occupies such a revered place in history, the plays themselves hold the answer.

Table of Contents

Life and Legacy of George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw’s life reads like one of his celebrated plays—a tale of resilience, intellect, and a relentless pursuit of social change. Born in 1856 in Dublin, Ireland, Shaw transcended the challenges of a tumultuous childhood to emerge as one of the most influential voices of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His razor-sharp wit, unflinching honesty, and fearless critique of society not only defined his character but also elevated him to legendary status. From his robust body of work to his unwavering commitment to progress, Shaw’s legacy offers lessons on how art can reflect—and reshape—the world around us.

Early Life and Education

Shaw was born into an economically unstable household, the youngest of three children. His father, a failed corn merchant prone to alcoholism, and his mother, a vocal coach, set the backdrop for a childhood tinged with hardship but rich in cultural exposure. Despite his aversion to formal education, Shaw displayed an insatiable appetite for self-study. Through books, music, and passionate debates, he found education on his own terms—an approach that would later characterize his free-thinking, nonconformist stance.

This self-directed learning shaped Shaw’s early worldview, particularly his disillusionment with societal hierarchies and capitalist power structures. By the time he moved to London in 1876, Shaw had realized that his voice could be a catalyst for change.

The Making of a Playwright and Social Thinker

In London, Shaw’s career began not in the theater but on the written page of political pamphlets and critiques. For nearly a decade, he struggled to find his footing as a novelist and critic. This period of obscurity steeled his resolve and honed his storytelling craft, but it wasn’t until he joined the Fabian Society in 1884—a socialist group advocating for gradual and democratic social reform—that he found a platform aligning with his ideals.

The marriage of his political beliefs and theatrical talent led Shaw to craft plays that challenged audiences to confront uncomfortable truths. His works often addressed perennially relevant topics—gender inequality, class dynamics, and the follies of organized religion and politics. Plays like Widowers’ Houses and Mrs. Warren’s Profession dared to hold a mirror to the injustices of Victorian society.

Detailed close-up image of the book spine ‘Man and Superman’ by George Bernard Shaw. [https://images.pexels.com/photos/4270164/pexels-photo-4270164.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=tinysrgb&dpr=2&h=650&w=940] Photo by cottonbro studio [https://www.pexels.com/@cottonbro]

His Influence on Literature and Society

Shaw redefined the theatrical landscape, proving that plays could be more than passive entertainment—they could incite dialogue and promote action. His sharp, satirical style and commitment to truth-telling earned him adoration and occasional controversy alike. Unlike his contemporaries, Shaw refrained from romantic escapism. Instead, he dramatized the grittier aspects of human existence, blending comedy with deep social commentary.

Beyond the stage, Shaw’s impact extended to political discourse and advocacy. From vigorous support for women’s suffrage to outspoken opposition to capitalism, he wasn’t content to merely write about change; he lived it. In 1925, Shaw was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, not only as a testament to his literary achievements but also as recognition of the way he used words to shape society. You can learn more about his biography through this resource [https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1925/shaw/biographical/].

Shaw’s Enduring Legacy

Passing away in 1950, Shaw left behind a literary legacy that remains relevant today. His more than 60 plays, countless essays, and political tracts continue to provoke thought and challenge societal norms. A visionary ahead of his time, Shaw believed in the potential of art to empower the oppressed and bridge divides—a mission that resonates now as much as it did in his own era. Read more about his contributions to culture and theater through this detailed analysis on Shaw’s lasting impact [https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Bernard-Shaw].

Key Themes and Style in Shaw’s Works

The works of George Bernard Shaw have long stood as a testament to the transformative power of theater. Combining humor, intellect, and bold critique, Shaw infused his plays with deeply reflective themes that push the audience to question societal norms and rethink their moral compass. At the heart of his writing lies a sharp focus on society’s failings, exploring issues that remain strikingly relevant today.

Exploration of Social Issues

Shaw consistently wielded his writing as a lens through which to examine some of the most pressing social issues of his time—and of ours. From stark depictions of class divisions to searing critiques of systemic corruption, his plays laid bare the inequalities embedded within societal structures.

Class Struggles and Economic Inequality: Decades before modern conversations on social equity gained traction, Shaw challenged the rigid class hierarchies that dictated people’s opportunities and quality of life. Plays like Pygmalion openly mocked and exposed the superficial markers of class, such as speech and behavior, suggesting how artificial and ultimately insignificant these distinctions can be. He called attention to how systematized inequality diminishes human potential while deliberately questioning the morality of capitalism. In Widowers’ Houses, for example, Shaw tactfully dramatized the greed and exploitation inherent in the landlord-tenant dynamic—a scenario that feels just as relevant in contemporary housing debates.

Corruption of Institutions: Shaw had no qualms about targeting the institutions that perpetuated societal ills. Organized religion, marriage, and even government fell under his scrutiny for their roles in maintaining injustice. He deconstructed the idea of unquestionable societal norms, particularly in plays such as Mrs. Warren’s Profession, where he boldly revealed the hypocrisies of moral conventions. It wasn’t just social critiques—it was a call to action. Shaw believed that theater could act as a mirror for audiences, forcing them to confront uncomfortable truths about the systems they supported, passively or otherwise. His biting commentary on institutional corruption can be further explored in this insightful piece here [https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/george-bernard-shaw/].

Philosophical and Moral Questions

Beyond social critique, Shaw’s plays often served as philosophical treatises, challenging audiences to grapple with profound moral questions. His work dove deep into the aspirations, contradictions, and ethical quandaries that define the human experience.

The Idea of the ‘Superman’: One of Shaw’s most provocative contributions was his exploration of Nietzschean philosophy, particularly the concept of the “superman.” In Man and Superman, Shaw interprets Nietzsche’s ideas through the framework of theater, marrying satire with a serious discourse on humanity’s potential for greatness. He portrayed the “superman” not as a solitary individual, but rather as humanity’s collective capacity to evolve toward higher ideals through intelligence, creativity, and moral courage. This wasn’t wishful thinking—it was Shaw’s way of challenging his audience to rise above mediocrity. Dive deeper into the philosophical underpinnings of Man and Superman by reviewing this resource here [https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V4ISSUE7/IJRPR15336.pdf].

Moral Dilemmas: Shaw deftly navigated the murky waters of right and wrong, often leaving audiences to ponder what morality truly means in a world defined by contradictions. Plays like Saint Joan encapsulate this tension. By portraying Joan of Arc as both a spiritual visionary and a tragic victim of institutional prosecution, Shaw forces the viewer to ask: Can any institution lay rightful claim to truth or justice? His nuanced approach avoided oversimplifications, often highlighting the gray areas where moral certainties dissolve. For more about Shaw’s intriguing philosophical ideas and their implications, explore this comprehensive overview here [https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1909/02/the-philosophy-of-bernard-shaw/].

By weaving these themes into his works, Shaw crafted an intellectual tapestry that continues to resonate across generations. His fearless critiques and philosophical depth prove that theater can be more than just an art form—it can be a catalyst for reflection and change.

Notable Works of George Bernard Shaw

Few playwrights have left as indelible a mark on literature as George Bernard Shaw. His works, celebrated for their wit, intellect, and unflinching critique of societal norms, continue to resonate with readers and theatergoers alike. Let’s delve into some of Shaw’s most significant plays, each a testament to his ability to challenge conventions and provoke thought.

Pygmalion (1912)

Panoramic view of a vibrant theater performance at Teatro Regio, Turin, Italy [https://images.pexels.com/photos/23812821/pexels-photo-23812821.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=tinysrgb&dpr=2&h=650&w=940]

Photo by Leonardo Luncasu [https://www.pexels.com/@leonardo-luncasu-1230168729]

At its core, Pygmalion explores the transformative power of language and culture, wrapped in Shaw’s critique of class divisions. The play focuses on Eliza Doolittle, a flower girl who takes speech lessons from Professor Henry Higgins in hopes of ascending the social ladder. Shaw uses their interactions to expose the absurdity of class distinctions, showing how status often hinges on superficial factors like accents and manners.

What sets Pygmalion apart is its enduring relevance and its evolution into the beloved musical My Fair Lady, which introduced Shaw’s social critiques to a global audience in a more whimsical format. But don’t let the charm of its songs fool you—Shaw never intended the story to have a romantic ending, insisting instead that Pygmalion challenge audiences to rethink society’s treatment of individuals based on arbitrary markers.

Explore more insights into Pygmalion’s key themes in this guide on Pygmalion Summary and Analysis [https://www.litcharts.com/lit/pygmalion/summary].

Saint Joan (1923)

Saint Joan captures the extraordinary life of Joan of Arc, reimagining her not as a distant religious figure but as a deeply human and visionary character. Shaw brings to the fore themes of individual faith, institutional corruption, and the often-painful consequences of challenging the status quo. Set during the tumultuous period of 15th-century France, the play is as much about Joan’s innate genius as it is about the societal forces that branded her a heretic.

In presenting Joan as a flawed yet gloriously resilient protagonist, Shaw questions the very structures—political, legal, and ecclesiastical—that claim to represent justice. The play ultimately invites audiences to ponder: What happens when one person’s faith collides with the consensus of the many? The play’s themes remain achingly relevant, especially in a world where individuality and conformity continue to clash.

Learn more about the themes of Saint Joan through this insightful breakdown: Saint Joan Themes [https://www.litcharts.com/lit/saint-joan/themes].

Man and Superman (1903)

In Man and Superman, Shaw tackles head-on the philosophical debate surrounding human purpose and societal evolution. Ostensibly a romantic comedy, the play brims with intellectual depth, blending laugh-out-loud moments with profound philosophical discourse. At the heart of the play lies Shaw’s interpretation of Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of the “superman”–an aspiration for humanity to transcend its limitations and strive for greatness.

The “Don Juan in Hell” scene stands out as a thought-provoking centerpiece, where Shaw examines concepts of heaven, hell, love, and morality with biting humor and intelligence. In doing so, Shaw rejects simplistic notions of good and evil, forcing his audience to consider life’s complexities.

For an in-depth exploration of Man and Superman, check out this analysis: Man and Superman Overview [https://literariness.org/2020/08/02/analysis-of-bernard-shaws-man-and-superman/].

Major Barbara (1905)

Major Barbara is one of Shaw’s most incisive commentaries on morality, religion, and the ethical ambiguities of capitalism. The play follows Barbara Undershaft, a Salvation Army officer whose resolve is tested when she confronts the economic realities of her father, a successful weapons manufacturer. Shaw juxtaposes Barbara’s ideals against her father’s cynical pragmatism, raising piercing questions about the compromises and hypocrisies society often makes in the pursuit of “good.”

Through sharp dialogue and complex characters, Shaw dismantles the romanticized notion that wealth and morality are mutually exclusive. Instead, he showcases the murky ethics of philanthropy and wealth, reminding us that noble causes often come with strings attached.

Dive deeper into the play’s interpretation of morality here: Major Barbara Themes and Discussion [https://www.litcharts.com/lit/major-barbara].

Arms and the Man (1894)

In Arms and the Man, Shaw takes a humorous yet pointed swipe at the idealization of war and heroism. Set during the Serbo-Bulgarian war, the play opens with the heroine, Raina, fantasizing about her fiancé’s military exploits. Her views are quickly upended by the arrival of Bluntschli, a practical and unromantic soldier who values survival over glory.

Through this satirical comedy, Shaw critiques the romanticized notion of war as a noble endeavor. Instead, he presents it as a messy, often absurd exercise driven by ego and misinformation. The play’s enduring humor and pacifist undertones make it a refreshing rebuttal to the bravado of traditional war narratives.

For further analysis, visit: Arms and the Man Study Guide [https://www.litcharts.com/lit/arms-and-the-man/summary].

Each of these plays showcases Shaw’s ability to weave sharp social commentary with unforgettable storytelling. Whether dissecting class, faith, or morality, Shaw’s works continue to challenge—and enchant—audiences worldwide.

The Impact of Shaw’s Works on Modern Literature and Society

George Bernard Shaw’s influence extends far beyond the confines of literature and theater. His sharp intellect and strong social conscience helped shape the way people approach storytelling and activism today. Below, we’ll explore Shaw’s enduring impact on society and how his ideas resonate in modern narratives.

Shaw’s Contribution to Social Reform

Shaw was no inactive observer when it came to societal issues; he sought to influence change directly. His involvement with the Fabian Society, a British socialist group advocating for gradual reform rather than revolution, marked a turning point not just in his career but also in how the intersection of art and politics was perceived. Shaw believed that knowledge and conversation were the bridges to social progress, and he employed his work to spark both.

Through plays like Widowers’ Houses, Shaw tackled pressing issues such as economic inequality and exploitation. These weren’t just theatrical performances—they were an indictment of the system itself. As a vocal member of the Fabian Society [https://fabians.org.uk/about-us/our-history/], Shaw contributed essays and speeches that mirrored the ideologies present in his works. The Society emphasized reforms based on intellectual debate and legislative action. Borrowing from this approach, Shaw used his plays as a public forum. When audiences watched a Shaw play, they weren’t merely entertained—they were asked to reckon with the justice and fairness of their world.

While Shaw valued debate, he also understood the necessity of practicality. His socialist theories often highlighted how systemic injustices could be reduced through policy and education reform, aligning with Fabian ideals of evolutionary socialism [https://www.britannica.com/topic/Fabian-Society]. By embedding these goals in his art, he pioneered a new role for the writer as both creator and reformer, pushing cultural boundaries and urging society to think critically.

Influence on Modern Storytelling

Shaw’s works echo in modern storytelling due to their layered characters and socially relevant messages. Most notably, his play Pygmalion has inspired numerous adaptations, turning Shaw’s ideas into cultural touchpoints that persist today. Adapted into the Broadway musical My Fair Lady and later a Hollywood film, Pygmalion carries Shaw’s critique of class and identity while bringing his sharp wit to wider audiences. These adaptations serve as prime examples of how Shaw’s ability to interrogate society found new life in contemporary media.

Shaw’s influence isn’t limited to theater; his work has shaped modern cinema as well. Themes of transformation and identity, central to Pygmalion, appear in countless films today. Shaw’s wit and focus on dialogue-driven storytelling paved the way for the “theater of ideas,” a concept echoed in contemporary dramas and satires. In this sense, Shaw’s legacy can be traced across works like Aaron Sorkin’s dialogue-heavy scripts or the morally complex narratives in films adapting his ideas further [https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/george-bernard-shaw/].

The depth of Shaw’s work also permeates theater education and performance. His characters—complex, flawed, and disarmingly human—have pushed playwrights to craft equally nuanced narratives. Actors interpreting Shaw’s roles often comment on the profound introspection required to embody his characters, a stark contrast to the one-dimensional figures of traditional melodrama. Influenced by Henrik Ibsen, Shaw introduced a realism that remains a hallmark of modern theater. You can learn more about Shaw’s broader contributions to literature here [https://medium.com/@nomanmatabbor/george-bernard-shaw-a-trailblazer-of-modern-theater-and-social-commentary-c0b8f3804346].

Shaw’s works refuse to grow old because they tap into primal human concerns: dignity, fairness, and self-understanding. Whether reshaped on Broadway stages or referenced in contemporary debates, Shaw’s ideas resonate, proving that a good story—like a good idea—is timeless.

Similar Authors

George Bernard Shaw’s distinct voice and legacy in literature naturally lead many readers to explore the works of similar authors who share thematic parallels, social critiques, or philosophical depths. Shaw’s ability to tackle societal issues with wit, satire, and intellectual rigor places him alongside a number of influential writers, past and present. If you marvel at Shaw’s profound blend of humor and pointed observation, these authors and playwrights might just offer a comparable experience.

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde, another Irish literary giant and contemporary of Shaw, shares his knack for piercing satire and keen social commentary. Wilde’s plays, such as The Importance of Being Earnest, dissect Victorian society with sharp wit and comedic elegance. Though he diverges from Shaw’s methodical explorations of moral and social dilemmas, both authors revel in exposing hypocrisy, whether it pertains to love, class, or politics. Wilde’s flamboyant touch and focus on aesthetic beauty contrast with Shaw’s more utilitarian approach, yet their shared pursuit of truth through theater makes Wilde an essential companion to Shaw’s work.

For broader insights into Wilde’s plays and their societal reflections, you can find more here: 20 Playwrights ALL Actors Should Know [https://www.cityheadshots.com/blog/playwrights].

Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Ibsen, often referred to as the “father of modern drama,” shares Shaw’s commitment to realism and social critique. His plays, including A Doll’s House and Hedda Gabler, confront issues like gender inequality, societal pressure, and individual freedom. Unlike Shaw’s frequent reliance on satire, Ibsen’s works often adopt a more serious and psychological tone, presenting characters trapped within suffocating social norms. If Shaw’s wit paves the way for introspection, Ibsen’s intense realism ensures that you walk the path.

Learn how Ibsen’s influence shaped modern theater through detailed analysis here [https://www.ranker.com/list/best-playwrights-ever/ranker-books].

Two stylish women in coats walking elegantly outdoors among modern architectural structures. [https://images.pexels.com/photos/6533066/pexels-photo-6533066.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=tinysrgb&dpr=2&h=650&w=940]

Photo by cottonbro studio [https://www.pexels.com/@cottonbro].

Anton Chekhov

Anton Chekhov, like Shaw and Ibsen, revolutionized modern drama with his keenly observed character studies and subtext-driven storytelling. Works such as The Cherry Orchard and Three Sisters delve into human emotions, relationships, and societal decay. While Shaw’s humor often shines through even in serious moments, Chekhov’s plays lean towards a melancholy introspection. The depth of Chekhov’s characters and his exploration of the passage of time make him a thought-provoking read for those drawn to Shaw’s thematic weight.

Find more information about Chekhov in this insightful list of Best Playwrights of All Time [https://www.stagemilk.com/best-playwrights/].

Bertolt Brecht

A stark contrast to Shaw in terms of theatrical structure but similar in intellectual and political ambition is Bertolt Brecht. Brecht’s epic theater aimed to provoke reflection and incite change rather than merely entertain. Plays like The Threepenny Opera and Mother Courage and Her Children highlight capitalist exploitation, war, and human resilience through innovative narrative techniques. Much like Shaw, Brecht used theater as a medium for activism, albeit with a more experimental and fragmented style.

Curious about how Brecht parallels Shaw’s revolutionary approach to theater? Check out this detailed overview: 20 Playwrights ALL Actors Should Know [https://www.cityheadshots.com/blog/playwrights].

William Shakespeare

Considered the epitome of dramatic writing, William Shakespeare’s works remain a touchstone for understanding society, power, and human frailty. While separated by centuries, Shaw admired Shakespeare’s command of language and his portrayal of timeless themes, often penning critiques that showcased both his reverence and his ambition to redefine theater. Shakespeare’s ability to blend comedic absurdity with tragic truths paved the way for Shaw’s genre-defying style. Plays such as Hamlet and King Lear explore themes overlapping with Shaw’s own: morality, societal constructs, and personal ambition.

Explore Shakespeare’s global literary influence and its connections to Shaw’s works here [https://www.goodreads.com/author/similar/5217.George_Bernard_Shaw].

August Strindberg

August Strindberg’s works delve into psychological depth and existential themes, offering a darker edge compared to Shaw’s satirical undertones. In plays like Miss Julie and The Father, Strindberg tackles gender dynamics, conflict, and mental fragility. His innovative use of naturalism in theater mirrors Shaw’s commitment to work as a vehicle for truth. Strindberg’s intensity challenges audiences to confront uncomfortable realities, aligning with Shaw’s penchant for presenting dialogues that linger long after the curtain falls.

For a closer look at Strindberg’s contributions to modern drama, explore this interactive map on Similar Authors [https://www.literature-map.com/george+bernard+shaw].

Each of these authors brings a unique perspective to themes that Shaw championed throughout his career. Whether you’re drawn to Wilde’s wit, Ibsen’s realism, Chekhov’s delicate poignancy, Brecht’s political vigor, Shakespeare’s grandeur, or Strindberg’s psychological intensity, these writers offer a rich collection of works that complement and enhance an appreciation for Shaw’s literary legacy.

Religious and Political Views

George Bernard Shaw was as enigmatic in his personal beliefs as he was in his writing. His views, often provocative and controversial, challenged the conventions of his time and continue to inspire debate. Navigating through organized religion and political ideologies, Shaw epitomized a free thinker whose principles evolved alongside his intellectual pursuits.

Religious Beliefs: A Theological Critic

Shaw’s relationship with religion was complex and layered, reflecting his broader skepticism of traditional authority. While he described himself as “a freethinker and critic of organized religion,” he did not completely dismiss the spiritual dimension of human existence. Shaw’s exploration of religious themes was less about faith and more about institutional critique, as seen in his play Saint Joan, which questions the morality of religious dogma while celebrating human conviction.

Unlike devout adherents or outright atheists of his era, Shaw straddled the line between skepticism and spirituality. He attacked the hypocrisies of organized religion, accusing it of being a tool for societal control. In a classic quip, he once jokingly remarked, “I’m an atheist, thank God,” encapsulating his critical approach to divine intervention.

To Shaw, morality did not stem from religion but from rational thought and societal progress. His stance illuminated the potential for personal ethics outside theological boundaries. A deeper dive into his religious views can be found on this page: George Bernard Shaw Religious Attitudes [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Bernard_Shaw].

Flat lay of an open Bible next to a notebook and pen, ideal for faith and study themes. [https://images.pexels.com/photos/8383412/pexels-photo-8383412.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=tinysrgb&dpr=2&h=650&w=940] Photo by Tara Winstead [https://www.pexels.com/@tara-winstead]

Political Ideologies: The Fabian Socialist

Few figures embodied such unwavering political convictions as George Bernard Shaw. An ardent and outspoken socialist, Shaw was a key member of the Fabian Society, a British socialist organization advocating for gradual reform. Unlike Karl Marx’s revolutionary socialism, Shaw supported an approach where political change occurred through education and policy rather than unrest.

Interestingly, Shaw wasn’t purely idealistic. He believed in practical reforms that lifted societal conditions, championing public health systems, women’s suffrage, and workers’ rights. In this, Shaw prefigured debates we still have today about societal equity and access to resources.

His plays often delivered biting critiques of capitalism and the class system. For example, in Widowers’ Houses, Shaw examines the ethics of wealth generated at the expense of marginalized communities. While he leaned toward socialism, his ideas stirred controversy—especially his controversial views on eugenics (a concept discredited in modern times) and admiration for certain authoritarian leaders, which alienated him from many progressive thinkers. Curious about Shaw’s take on socialism? Read more via this resource on George Bernard Shaw and the Fabian Society [https://www.quora.com/Was-George-Bernard-Shaw-a-communist-or-socialist].

The Intersection of Religion and Politics in Shaw’s Works

It’s impossible to discuss Shaw’s beliefs without acknowledging how seamlessly he wove these convictions into his art. Plays such as Major Barbara explore the tenuous intersection of morality, religion, and economic interests. Through this lens, Shaw dissected how institutions, religious or political, often manipulated morality for their own gain.

He used the stage to question societal norms, urging audiences to reconsider their stances on organized faith and governance. Shaw’s belief in humanity’s potential for enlightenment shines across his body of work, offering a nuanced perspective that transcends mere ideology.

In a world increasingly polarized by religious and political dogma, Shaw’s ideas encourage us to revisit the gray areas—reminding us that real progress often occurs not at the extremes but in the thoughtful exchange of ideas. Detailed insights into Shaw’s life and ideologies are available here [https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Bernard-Shaw].

Who Should Read Them

George Bernard Shaw’s works bridge intellectual critique and entertainment, delving into societal norms, moral dilemmas, and human behavior. But who exactly stands to gain from reading his plays? If you’re wondering whether Shaw’s canon is for you, consider these categories of readers:

Lovers of Satire and Social Commentary

If you find joy in questioning the status quo and uncovering the deeper meanings behind accepted societal norms, Shaw is likely to become a favorite. His plays, such as Major Barbara or Mrs. Warren’s Profession, often dissect the hypocrisies of organized religion, capitalism, and Victorian morality. For readers who value satire, Shaw transforms typical theater-going into an intellectual workout—challenging preconceptions and reshaping beliefs.

Shaw is particularly appealing for those who value bold writing that speaks truth to power. Imagine a playwright who critiques society not through quiet metaphors but with sharp-tongued characters delivering biting, uncomfortable truths. If that excites you, diving into his works could feel like a long conversation with an unapologetic but brilliant friend. Explore a guide for Shaw’s must-reads here [https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/73765.Best_of_George_Bernard_Shaw].

Fans of Philosophical Drama

Shaw’s works aren’t just plays—they’re discussion boards transformed into theatrical performances. If you’ve ever wondered about life’s big questions—on love, existence, morality, or the aspirations of humanity—then his plays, particularly Man and Superman and Saint Joan, will resonate deeply. His dramas challenge audiences not just to empathize with his characters but to reflect on their own values, often flipping conventional thinking on its head. For Shaw, theater is debate made visible; if you enjoy grappling with thorny moral quandaries, few works provide as rich a canvas.

Shaw likened the theater to a public forum where ideas could not only thrive but also collide. Imagine moral dilemmas unfolding in real-time through characters that mirror some part of your own internal debate. Not sure where to start? Check out this list [https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/109933.The_Best_of_George_Bernard_Shaw] of his most impactful works.

Students and Scholars of Literature

No literary education is complete without delving into some of Shaw’s most celebrated texts. His melding of intellectual rigor with dramatic flair makes him a cornerstone in studies of modern theater. For aspiring playwrights, his ability to question societal structures while entertaining audiences is both a guidebook and an inspiration. In academic terms, Shaw offers endless material for exploring themes of identity, power, and justice.

Scholars often marvel at his character construction and mastery in balancing absurdity with profound insight. If you’re piecing together literature’s evolutionary narrative, Shaw’s influence—positioned between Ibsen’s realism and Brecht’s epic theater—is unmistakable. For deeper insights on his theatrical legacy, this useful forum might help: GB Shaw Recommendations [http://www.online-literature.com/forums/showthread.php?20516-G-B-Shaw-recommendations].

Theater Enthusiasts and Performing Artists

For actors, directors, and anyone captivated by the stage, Shaw’s works provide a challenging yet rewarding experience. His characters are not one-dimensional archetypes but deeply nuanced beings grappling with societal constraints and inner turmoil. This complexity offers actors a rare chance to inhabit roles that demand both intellectual acumen and emotional finesse.

Directors and theater aficionados, too, will find Shaw indispensable for understanding how the stage can double as a vehicle for social change. His fusion of wit, commentary, and craftsmanship brings his works alive in performance, proving that great art often mirrors complex realities. Curious about which plays to experience first on stage? Begin here: Shaw’s Greatest Hits [https://thegreatestbooks.org/authors/5478].

Readers Seeking Timeless Themes

Shaw’s plays don’t just resonate with specific groups—they’re broadly applicable because they tackle universal themes. Whether you’re interested in societal revolutions, personal growth, or power dynamics, his works endure because they speak to everyone at the heart of human experience. If you’ve ever questioned why things are the way they are—or dreamt of how they could be different—you’re the reader Shaw had in mind.

Who else might enjoy Shaw? Those drawn to timeless explorations of class, ambition, and morality—concepts as relevant in today’s world as in Shaw’s. For an overview of these lasting themes, visit here [https://www.quora.com/Which-of-George-Bernard-Shaws-work-should-I-read-first].

By redefining the possibilities of theater and challenging audiences to think, Shaw crafted stories for the curious, the critical, and the relentlessly introspective. Whether you’re looking for sharp satire or profound philosophical insights, there’s likely a Shaw play that feels tailor-made just for you.

Conclusion

George Bernard Shaw’s works endure because they were designed to provoke, not pacify. Through plays like Pygmalion, Saint Joan, and Man and Superman, he turned theater into a space of sharp inquiry and social reflection. Shaw wasn’t afraid to challenge his audience—he expected them to question, laugh, and even squirm. His humor masked hard truths, while his intellect pushed the boundaries of what drama could achieve.

Today, his legacy stands as a testament to the power of art as a tool for change. Shaw reminds us that great writing doesn’t just entertain—it challenges the world to be better. Where humor and critique collide, Shaw’s voice still echoes, urging us to think more deeply about the society we live in and the roles we play within it.