In a world of constant change and uncertainty, the ancient philosophy of Stoicism offers timeless wisdom for navigating life’s challenges with resilience and inner peace. But what does it really mean to be “stoic”? Far more than the common misconception of emotional suppression or indifference, Stoicism represents a rich philosophical tradition focused on developing virtue, wisdom, and emotional resilience through rational thought. This guide explores the origins, principles, and modern applications of Stoic philosophy, providing practical insights for incorporating this ancient wisdom into your everyday life.

The Origins of the Word “Stoic”

The Stoa Poikile (Painted Porch) in ancient Athens where Stoic philosophy originated

The term “Stoic” derives from the Greek word “stoa,” referring to the Stoa Poikile or “painted porch” in Athens where the philosophy was first taught. Around 300 BCE, a merchant named Zeno of Citium began teaching at this public colonnade after being shipwrecked and losing nearly everything. What began as personal tragedy transformed into one of history’s most influential philosophical schools.

Zeno’s shipwreck proved fortuitous—he later joked, “I made a prosperous voyage when I suffered shipwreck.” In Athens, he encountered the teachings of Socrates through Cynic philosophers and developed a new philosophical approach that balanced practicality with virtue. Unlike many philosophical schools named after their founders, Stoicism took its name from the location where its adherents gathered—a testament to Zeno’s humility.

Stoicism flourished for over 500 years, evolving through three major historical phases:

- Early Stoa (300-129 BCE): Founded by Zeno and systematized by Chrysippus, establishing the theoretical foundations

- Middle Stoa (129-30 BCE): Led by Panaetius and Posidonius, who brought Stoicism to Rome

- Late Stoa (30 BCE-180 CE): The Roman period featuring Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius, focusing on practical ethics

During these centuries, Stoicism became one of the dominant philosophical schools of the Greco-Roman world, influencing countless individuals from slaves to emperors. The philosophy spread throughout the Mediterranean, eventually becoming a cornerstone of Western philosophical thought.

Core Principles of Stoic Philosophy

Stoicism is built upon a comprehensive system of thought organized into three interconnected areas: Logic (how to reason correctly), Physics (understanding the natural world), and Ethics (how to live virtuously). While these areas form a cohesive whole, the ethical teachings remain the most accessible and practical aspect of Stoicism today.

The four cardinal virtues of Stoicism: wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance

The Four Virtues

At the heart of Stoic ethics are the four cardinal virtues, which the Stoics believed were both necessary and sufficient for a good life:

Wisdom (Phronesis)

The ability to navigate complex situations with clear judgment and understanding. Wisdom involves knowing what is within your control and what isn’t, making sound decisions based on reason rather than impulse.

Courage (Andreia)

Not merely physical bravery, but moral courage—the strength to face challenges, stand by your principles, and endure hardship without complaint. As Seneca noted, “Sometimes even to live is an act of courage.”

Justice (Dikaiosyne)

Treating others with fairness, integrity, and respect. The Stoics viewed humans as naturally social beings with obligations to their communities. Marcus Aurelius called justice “the source of all the other virtues.”

Temperance (Sophrosyne)

Self-discipline and moderation in all things. Temperance means controlling destructive emotions and avoiding excess, finding the middle path between extremes.

The Dichotomy of Control

Perhaps the most practical Stoic principle is the dichotomy of control—distinguishing between what we can and cannot influence. As Epictetus taught: “Some things are within our power, while others are not.”

Living According to Nature

The Stoics advocated “living according to nature,” meaning aligning our actions with both universal reason and our nature as social, rational beings capable of virtue.

Start Your Stoic Journey Today

Want to apply these timeless principles to your life? Download our free “7-Day Stoic Principles Challenge” and begin practicing Stoicism in practical, meaningful ways.

The Stoic View of Emotions

Contrary to popular belief, Stoics didn’t advocate eliminating emotions entirely. Rather, they distinguished between unhealthy, irrational passions (pathos) and healthy, rational emotions (eupatheiai). The goal was not emotional suppression but emotional intelligence—responding to events with appropriate feelings based on accurate judgments.

Unhealthy Passions:

- Fear: Irrational aversion to expected harm

- Distress: Irrational contraction of the mind

- Lust/Craving: Irrational desire for expected good

- Pleasure: Irrational elation over apparent good

Healthy Emotions:

- Caution: Rational avoidance of genuine harm

- Wish: Rational desire aligned with virtue

- Joy: Rational delight in genuine good

The Stoic goal was apatheia—not apathy in the modern sense, but freedom from disturbing, irrational emotions. This state allows for clear thinking and virtuous action even in difficult circumstances.

“Make the best use of what is in your power, and take the rest as it happens. Some things are up to us and some things are not up to us.”

— Epictetus, Enchiridion

Key Stoic Thinkers

While many philosophers contributed to Stoic thought, three Roman Stoics have had the most lasting influence through their surviving writings:

Seneca (4 BCE – 65 CE)

A Roman statesman, playwright, and advisor to Emperor Nero, Seneca wrote extensively on applying Stoic principles to everyday challenges. His letters and essays address topics like anger management, dealing with grief, and finding tranquility amid chaos. Despite his wealth and political power, Seneca emphasized that external success was ultimately indifferent to true happiness.

Epictetus (55 – 135 CE)

Born a slave, Epictetus gained freedom and became one of history’s most influential philosophical teachers. His teachings, recorded by his student Arrian in the Discourses and Enchiridion, focus on personal freedom through controlling our reactions to events. His famous dichotomy of control remains one of Stoicism’s most practical contributions.

Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180 CE)

Roman Emperor from 161 to 180 CE, Marcus Aurelius wrote his Meditations as personal notes never intended for publication. These private reflections reveal a powerful mind wrestling with the challenges of leadership, mortality, and maintaining virtue amid adversity. His work remains one of the most accessible introductions to Stoic thought.

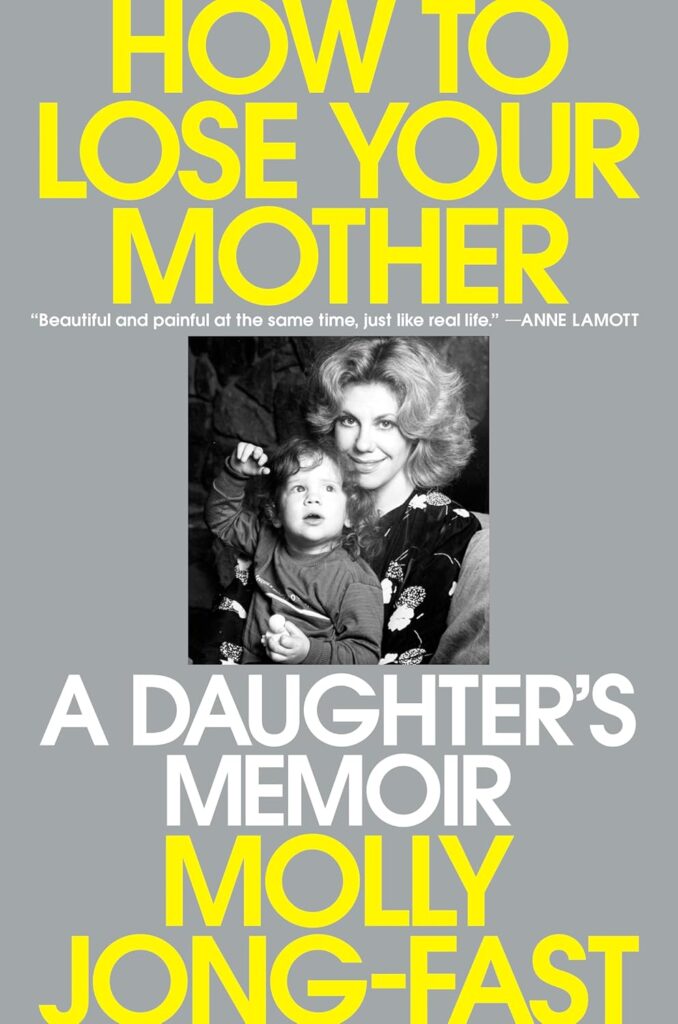

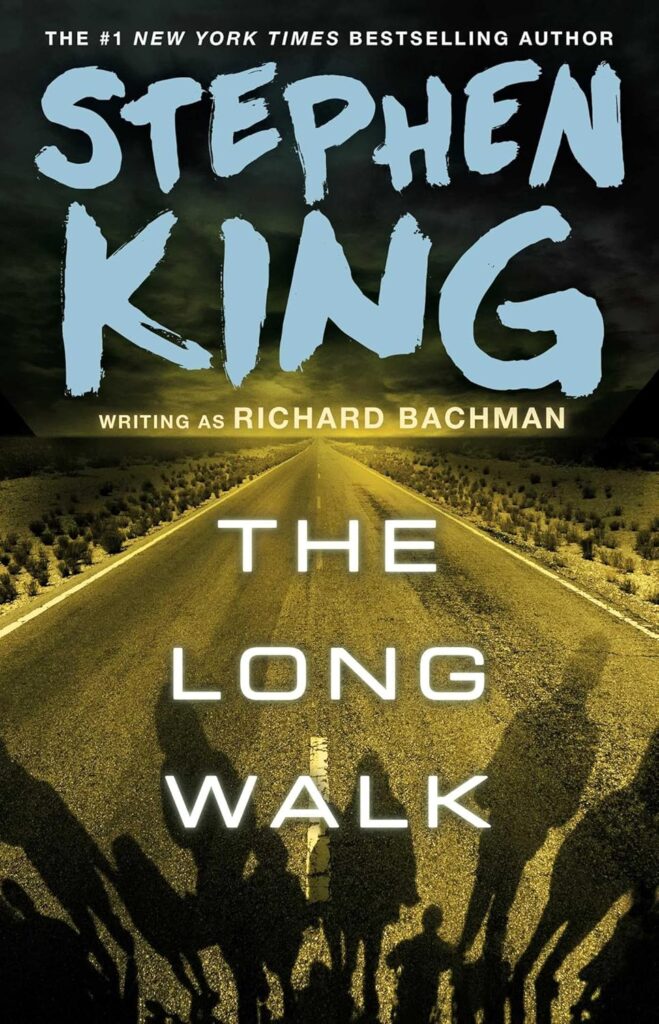

Explore the Wisdom of the Stoics

Ready to dive deeper into Stoic philosophy? These essential books provide direct access to the minds of history’s greatest Stoic thinkers.

Modern Interpretations of Being Stoic

Today, the word “stoic” has taken on a meaning somewhat different from its philosophical roots. In common usage, being “stoic” often refers to someone who remains calm under pressure, shows little emotion, or endures hardship without complaint. While this captures some aspects of Stoicism, it misses the rich philosophical framework that underlies the original concept.

Modern application of Stoic principles through reflection and journaling

Contemporary Stoicism

The 21st century has seen a remarkable resurgence of interest in Stoicism as a practical philosophy for modern life. This revival has been fueled by several factors:

- Recognition that many modern psychological approaches, particularly Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), have roots in Stoic ideas

- Growing interest in mindfulness and emotional resilience

- The search for meaning and ethical frameworks in an increasingly complex world

- Accessibility of Stoic texts and new interpretations through books, podcasts, and online communities

Contemporary Stoicism adapts ancient wisdom to modern contexts while maintaining core principles. Modern Stoics typically focus on:

Mindfulness Practice

Daily reflection and awareness exercises to examine judgments and impressions before giving them assent. Modern Stoics often keep journals, practice meditation, or use structured exercises to develop this awareness.

Rational Emotion Management

Using reason to examine emotional responses and develop healthier reactions to challenging situations. This doesn’t mean suppressing emotions but understanding their cognitive basis.

Virtue Ethics in Daily Life

Applying the four virtues to everyday decisions and relationships, focusing on character development rather than rigid rules or outcome-based ethics.

Stoic Exercises for Modern Life

The ancient Stoics developed practical exercises to cultivate virtue and resilience. Many of these can be adapted for contemporary use:

Morning Preparation

Begin each day by anticipating challenges and preparing to face them virtuously. Marcus Aurelius wrote: “When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous, and surly.”

Evening Reflection

End each day by reviewing your actions. What went well? Where did you fall short? How can you improve tomorrow? Seneca practiced this nightly review: “When the light has been removed… I examine my entire day and go back over what I’ve done and said.”

Negative Visualization (Premeditatio Malorum)

Periodically imagine losing things you value—health, relationships, possessions—to reduce unhealthy attachment and increase gratitude. This isn’t pessimism but a way to appreciate what you have.

The View From Above

Mentally step back to see your concerns from a cosmic perspective. This exercise helps reduce anxiety about trivial matters by placing them in a larger context.

“You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Daily Stoic Wisdom in Your Inbox

Receive a daily Stoic meditation to start your morning with clarity and purpose. Each email includes a quote from a Stoic philosopher and a brief reflection on applying it to modern life.

How Stoicism Differs From Other Philosophies

To fully understand Stoicism, it helps to compare it with other philosophical approaches that addressed similar questions about the good life, emotions, and human flourishing.

Comparison of major Hellenistic philosophical schools

| Philosophy | View of the Good Life | Approach to Emotions | View of External Goods | Key Difference from Stoicism |

| Stoicism | Living virtuously in accordance with nature and reason | Transform through rational examination; distinguish between healthy and unhealthy emotions | Preferred indifferents—valuable but not essential for happiness | — |

| Epicureanism | Achieving pleasure (defined as absence of pain) and tranquility (ataraxia) | Seek pleasant emotions, avoid painful ones | Valuable only if they produce pleasure; many are unnecessary | Focuses on pleasure rather than virtue as the highest good |

| Aristotelianism | Eudaimonia through virtuous activity and moderate external goods | Moderation—the golden mean between excess and deficiency | Necessary components of happiness | Requires some external goods for happiness |

| Cynicism | Virtue through rejection of convention and material comforts | Reject social emotions; embrace natural simplicity | Actively harmful distractions from virtue | More radical rejection of social norms and comforts |

| Buddhism | Liberation from suffering through enlightenment | Detachment from desires that cause suffering | Attachments that perpetuate suffering | Metaphysically non-dualist; focuses on mindfulness rather than reason |

Stoicism vs. Epicureanism

The Stoics engaged in vigorous debate with the Epicureans, another major Hellenistic school. While both aimed at tranquility, they differed fundamentally on how to achieve it:

Stoicism

- Virtue is the only true good

- Engage actively with society

- Accept fate (amor fati)

- Emotions should be examined rationally

- Providence guides the universe

Epicureanism

- Pleasure (absence of pain) is the highest good

- Withdraw from politics and public life

- Avoid pain and disturbance

- Emotions should be managed for tranquility

- Atoms move randomly; no providence

Stoicism vs. Modern Psychology

Many modern psychological approaches show remarkable parallels with Stoic principles:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) shares the Stoic insight that our distress comes not from events themselves but from our judgments about them

- Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), developed by Albert Ellis, was explicitly influenced by Stoicism

- Logotherapy, created by Viktor Frankl, echoes the Stoic emphasis on finding meaning even in suffering

- Positive Psychology research on character strengths aligns with the Stoic focus on virtue

The key difference is that modern psychology typically aims at subjective well-being, while Stoicism emphasizes virtue regardless of whether it produces pleasant feelings.

Practical Examples of Stoic Behavior Today

Stoicism isn’t just an abstract philosophy—it provides practical guidance for navigating real-world challenges. Here are examples of how Stoic principles can be applied in various aspects of modern life:

Demonstrating Stoic resilience during modern challenges

In the Workplace

Dealing with Criticism

Non-Stoic Response: Taking feedback personally, becoming defensive or discouraged.

Stoic Response: Separating your worth from others’ opinions, focusing on what you can learn, and using criticism as an opportunity for growth.

Handling Setbacks

Non-Stoic Response: Blaming others, complaining about unfairness, or giving up.

Stoic Response: Focusing on what’s within your control, learning from failure, and persisting with adjusted strategies.

Managing Stress

Non-Stoic Response: Becoming overwhelmed, procrastinating, or using unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Stoic Response: Breaking challenges into manageable parts, focusing on present actions rather than worrying about outcomes.

In Relationships

During Conflict

Non-Stoic Response: Reacting emotionally, saying things you’ll regret, or holding grudges.

Stoic Response: Pausing before responding, seeking to understand the other person’s perspective, and focusing on resolution rather than being right.

When Disappointed by Others

Non-Stoic Response: Feeling betrayed, ruminating on how others should have behaved differently.

Stoic Response: Remembering that others’ actions are outside your control, adjusting expectations based on human nature, and choosing your response wisely.

Facing Personal Challenges

Health Problems

Non-Stoic Response: “Why me?” thinking, catastrophizing, or becoming defined by illness.

Stoic Response: Accepting what cannot be changed while taking appropriate action, maintaining perspective, and focusing on what you can still do rather than what you cannot.

Financial Setbacks

Non-Stoic Response: Panic, shame, or making impulsive decisions.

Stoic Response: Distinguishing between needs and wants, adapting with dignity, and using adversity as an opportunity to practice virtue.

Loss and Grief

Non-Stoic Response: Becoming overwhelmed by grief or denying natural emotions.

Stoic Response: Acknowledging natural grief while maintaining perspective, finding meaning in loss, and honoring the deceased through virtuous living.

“It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.”

— Epictetus

Stoic Decision-Making Framework

When facing difficult choices, this Stoic decision-making process can help:

- Clarify what’s in your control — Separate what you can influence from what you cannot

- Identify the virtuous action — Ask which option best expresses wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance

- Consider preferred indifferents — Among virtuous options, which best promotes health, wealth, etc.

- Prepare for all outcomes — Mentally rehearse how you’ll respond virtuously to different results

- Act decisively — Once you’ve deliberated, commit fully to your chosen course

Daily Stoic journaling practice with reflections on virtue and character

Modern Stoics: Real-World Examples

Many historical and contemporary figures have embodied Stoic principles:

- Admiral James Stockdale credited Stoicism, particularly Epictetus, with helping him survive seven years as a prisoner of war in Vietnam

- Nelson Mandela demonstrated Stoic resilience during his 27-year imprisonment and forgiveness afterward

- Coach John Wooden applied Stoic principles in his focus on character development rather than winning

- Psychologist Viktor Frankl showed Stoic wisdom in finding meaning in suffering during his Holocaust imprisonment

Begin Your Stoic Practice Today

Ready to apply Stoic wisdom to your daily challenges? Our comprehensive guide provides practical exercises, reflections, and strategies for living more virtuously and finding tranquility in a chaotic world.

Common Misconceptions About Stoicism

True Stoicism versus common misconceptions

Myth: Stoics suppress all emotions

Reality: Stoics distinguish between harmful passions and healthy emotions. They don’t suppress feelings but examine them rationally. The goal is not emotional numbness but appropriate emotional responses based on accurate judgments.

Myth: Stoicism means enduring suffering without complaint

Reality: While Stoics do emphasize resilience, they also advocate taking practical action to improve situations when possible. Stoicism is about responding virtuously to circumstances, not merely enduring them passively.

Myth: Stoicism promotes detachment from others

Reality: Stoics believed humans are naturally social beings with obligations to their communities. Justice and proper social relationships are central to Stoic ethics. Marcus Aurelius wrote, “We were born to work together.”

Myth: Stoicism is pessimistic

Reality: While Stoics prepare for adversity, they do so to appreciate the present more fully. Practices like negative visualization aim to increase gratitude and joy, not pessimism. The Stoic goal is tranquility and flourishing, not resignation.

Embracing Stoicism in Modern Life

Stoicism offers timeless wisdom for navigating life’s complexities with resilience, wisdom, and virtue. Far from being a philosophy of emotional suppression or mere endurance, Stoicism provides a comprehensive framework for living well—focusing on what we can control, developing our character, and finding meaning even in challenging circumstances.

The journey toward Stoic wisdom is ongoing and practical. It involves daily reflection, mindful choices, and a commitment to aligning our actions with our highest values. Whether facing workplace stress, relationship challenges, or personal setbacks, Stoic principles offer guidance for responding virtuously and maintaining inner tranquility.

As you incorporate these ancient teachings into your modern life, remember that progress, not perfection, is the goal. The Stoics themselves acknowledged that the ideal of the perfectly wise Sage was rarely if ever achieved. What matters is the ongoing effort to improve—what the Stoics called prokopē, or making progress.

“Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Continue Your Stoic Journey

Join thousands of others learning to apply ancient Stoic wisdom to modern challenges. Get our free 7-day email course on practical Stoicism and receive weekly insights on living virtuously in today’s world.