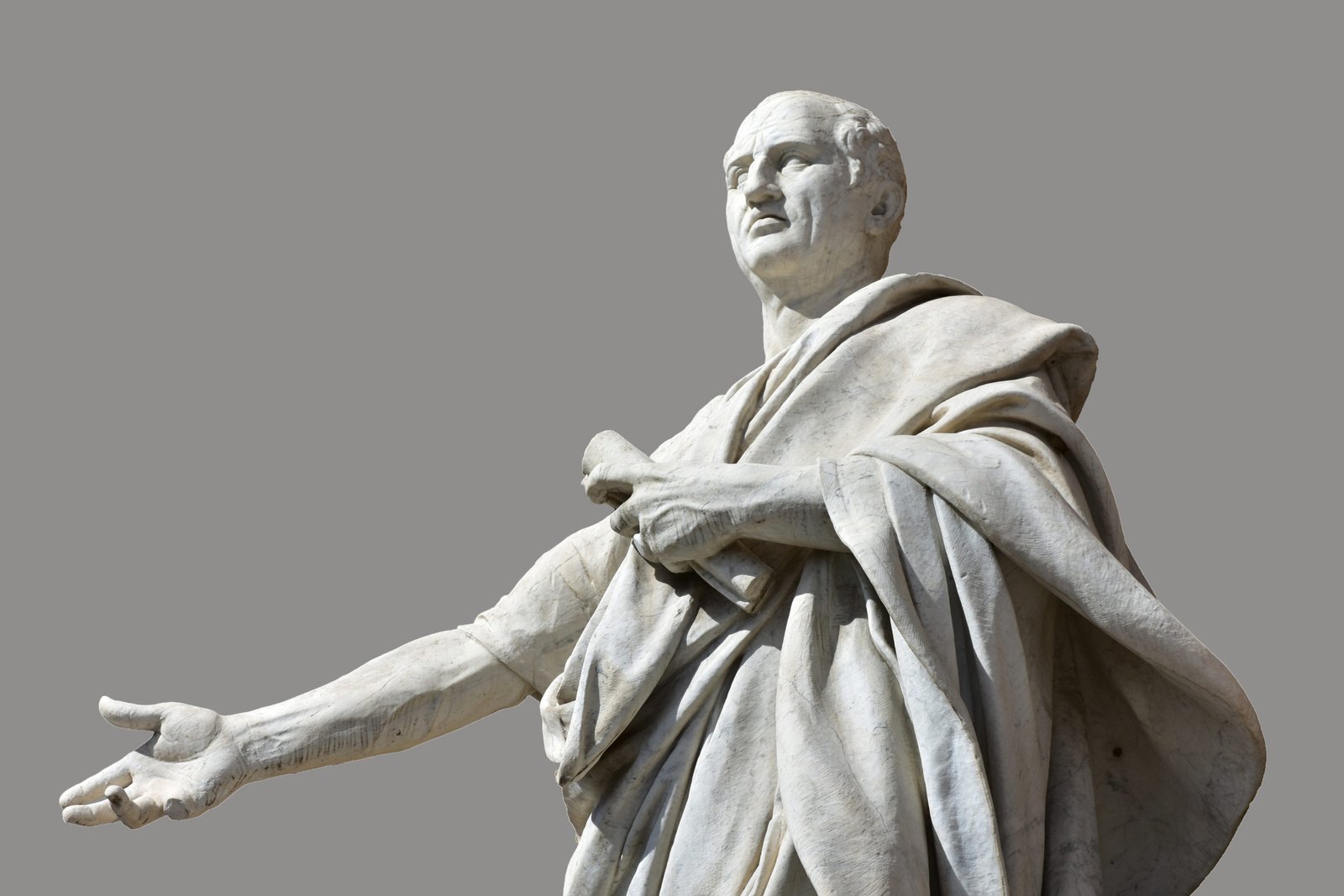

It’s funny, isn’t it? How a name like Cicero feels so distant and weighty, like it belongs in a museum or a thick textbook gathering dust. But here’s the thing: this ancient Roman statesman, philosopher, and all-around intellectual powerhouse still has a way of reaching across centuries to grab you by the shoulders—especially when you start wondering what makes a life “good.” Born in 106 BCE, Cicero lived through the messy, chaotic collapse of the Roman Republic (seriously, think political backstabbing, literal assassinations, the works). Yet, in the midst of that, he obsessed over the same things we do today: virtue, purpose, and how to live in a way that feels meaningful.

What’s wild to me is how his ideas aren’t just relevant—they’re personal. He believed the “good life” wasn’t about chasing pleasure or avoiding pain, but about living with integrity, contributing to society, and finding harmony between our higher principles and everyday actions. And maybe that’s the secret, right? That the pursuit of a “good life” isn’t some distant, philosophical debate. It’s here. Today. Something we inch closer to (or away from) with every choice we make.

Table of Contents

The Cornerstones of Cicero’s Philosophy on the Good Life

Cicero’s take on what makes life truly “good” is both refreshingly straightforward and profoundly challenging. He believed that a good life wasn’t about empty pleasures or material distractions—it was about the choices we make, the kind of people we strive to be. Virtue was his compass, the unshakable foundation that guided everything else, and he believed it came with rewards far deeper than fleeting happiness. It’s not the easy route, but let’s be real—when is anything worth it ever easy?

Virtue as the Foundation of Happiness

In Cicero’s eyes, living well came down to cultivating specific virtues. He wasn’t vague about what these were, either. Four key pillars defined his idea of goodness: wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance. They weren’t optional—they were the blueprint for happiness.

- Wisdom: For Cicero, understanding the world and our place in it mattered deeply. Wisdom meant making thoughtful choices, not just for immediate gains but for the bigger picture. It’s that ability to step back, see the forest instead of the trees, and ask—what’s actually worth my time and energy?

- Justice: Here’s the kicker—being good, for Cicero, wasn’t just about personal fulfillment. Justice is about fairness and showing up for others. It’s like a quiet reminder that playing dirty might win you the game, but it’s a lousy way to win at life.

- Courage: Life will throw curveballs; we all know it. Courage, as Cicero saw it, wasn’t just about bravery on a battlefield (though he deeply respected that). It was about standing firm in your values, even when it costs you.

- Temperance: Balance might be the hardest virtue of all to master. Cicero emphasized the need for self-restraint—not suppressing your desires entirely but keeping them in check. Kind of like learning to walk a tightrope between indulgence and denial.

By placing virtue at the center of his philosophy, Cicero was essentially saying: If you want to be happy, start by being good. He wasn’t preaching perfection, though. It’s a journey, right? You stumble, you learn, you adjust, and hopefully, you grow.

(Here’s a deeper dive into Cicero’s thoughts on happiness and virtue if you want to explore further.)

The Interconnection Between Virtue and Contentment

Let me ask you this: When have you felt most at peace with yourself? Not in some Instagram-perfect, sunset-meditation kind of way, but when you’ve truly felt grounded, like you’re on the right path? For Cicero, that feeling wasn’t some mystical state—it was the natural outcome of living morally.

He believed that virtue and true contentment were inseparable, like two sides of the same coin. Why? Because when you’re morally grounded, you’re not constantly looking over your shoulder or battling that soul-crushing guilt that creeps in after making a selfish choice. He thought moral goodness had a way of clearing the mental clutter, aligning your actions with your ideals so that what you do feels right. That’s any kind of inner peace worth having, don’t you think?

Cicero was all about this idea that life falls into harmony when you commit to virtuous living. Yes, bad things will still happen—loss, betrayal, disappointment. He got that; after all, he lived in a time of political chaos that makes modern drama look tame. But even amid the storm, Cicero believed you could find a quiet center through moral integrity. It’s not that virtue shields you from suffering—it’s what helps you weather it with dignity.

He goes into this in remarkable detail in works like On the Good Life (you can check out a summary of the themes here). It’s inspiring to think that over two thousand years ago, someone was writing about these same human struggles we still wrestle with today.

Maybe that’s why his message sticks with me. He wasn’t promising a quick fix or an easy answer. Instead, Cicero offers this almost radical idea: that happiness is something you build—not through stuff or status, but through the person you become. It’s hard work, yes. But something about that difficulty is what gives it depth.

Cicero’s Emphasis on Eloquence and Communication

When I think about Cicero, one word jumps to the front of my mind—voice. Not just any voice, but the kind that stops you mid-thought, makes you sit up, and truly listen. For Cicero, eloquence wasn’t just about speaking well. It was a virtue, a way of linking head and heart, reason and emotion, to inspire action. Communication, to him, wasn’t “just part of the job.” It was the job. And let’s be honest, are there any areas of life where being a better communicator doesn’t help? I’m still looking.

This emphasis is one of the reasons Cicero’s insights feel so timeless. His belief in the transformational power of speech—rooted in character and knowledge—offers lessons not just for ancient hotshots in the Roman Forum but for all of us navigating modern life. After all, life is relationships, right? And relationships thrive (or fall apart) on communication.

The Role of Eloquence in Leadership and Society

If you’ve ever been in a room where someone commanded attention—not because they yelled louder, but because every word hit like they meant it—you know what I’m talking about. Cicero believed that kind of eloquence had the power to build a better society. It wasn’t just about smooth talk or showing off an impressive vocabulary. Nope. For him, true eloquence combined virtue with clarity, passion, and purpose.

Here’s why this matters: leaders rely on words to motivate, collaborate, and unite. In Cicero’s world (and honestly, ours too), miscommunication or manipulation could destroy cities, relationships, entire governments. Think about it—how many modern conflicts boil down to bad communication paired with a lack of trust? Cicero argued that effective speech had to be grounded in virtue and truth. You couldn’t fake it—you had to be it.

Take a cue from his pivotal speeches, like his infamous Cataline Orations, where he faced betrayal and conspiracy head-on. Cicero’s ability to weave passion with logic didn’t just strengthen his personal credibility—it strengthened the state. His words could rally, criticize, and convince without losing sight of justice. Can you imagine what politics (or even personal disputes!) would look like if people made clarity and fairness their first priority when they spoke?

Honestly, Cicero’s ideas about the role of eloquence aren’t just for would-be politicians. They’re for all of us. Whether it’s advocating for yourself at work, resolving conflicts in relationships, or standing up for what you believe in, speaking from both the head and the heart is key. One of his lessons on this topic is explored beautifully here.

Mastery of Language Through Historical Context

Look, Cicero didn’t wake up one day speaking wisdom like he swallowed a thousand philosophers. He saw eloquence as something to be built, and the foundation, in his view, was history. He treated history like a textbook for the soul, analyzing past events to understand how language could mold decisions, communities, and legacies. And let’s be real—if you’ve never replayed a tough conversation in your head and rephrased things to imagine a better outcome, you’ve already dabbled in borrowing from your personal “history.”

Here’s the cool part: for Cicero, history wasn’t just “the past.” It was a living resource. He believed the events, speeches, and choices of those who came before us could teach us how to use language to build rather than destroy. Armed with insights from past leaders, mistakes, and victories, Cicero argued that we could all learn to respond to life with grace instead of reflex. His own speeches, influenced by studying figures like Demosthenes and Isocrates, showed that a message isn’t just about what you say—it’s how you shape it.

For me, this gets personal. I’ve realized that words, when chosen carefully, can either fence people out or pull them in. Cicero’s emphasis on studying context—historical, emotional, situational—reminds me that every conversation is part of a bigger story. One of his sharpest lessons on this subject? We have to listen before we speak. We can’t understand context if we’re the only ones talking. You can explore more about Cicero’s thoughts on rhetoric in the context of history here.

What I love most about Cicero’s advice is how practical it feels. Mastery of language through historical and situational awareness isn’t elitist; it’s compassionate. It’s saying, “I see where you’ve been and I’m meeting you there, so we can move forward together.” That’s an incredible thing, isn’t it? To use words not as weapons or shields but as bridges. And in a world where everyone seems to be yelling over each other, Cicero’s approach feels like a breath of fresh air.

The Role of Philosophy and Knowledge in the Good Life

When I think about the term “the good life,” it sounds almost too simple, doesn’t it? Like a phrase someone might throw around in a self-help book or on a motivational podcast. But strip away the fluff for a moment, and you’re left with fundamental questions: What does it mean to live well? To make life count? For Cicero—and for anyone who’s willing to sit with these questions—the answers often begin in philosophy. It’s not just about lofty debates or abstract theories; philosophy, at its best, gives us tools to navigate life. It’s like learning how to read a map when you’re lost in the maze of daily grind and big existential fears.

Philosophy as a Path to Critical Thinking and Self-Awareness

Have you ever been halfway through a bad decision and thought, “Wait, how did I even get here?” Yeah, me too. Life moves fast, and it’s ridiculously easy to act out of habit or emotion without stopping to think things through. That’s where philosophy can step in—not as a fix-it-all, but as a mirror and a magnifying glass rolled into one. A way to see the bigger ethical picture while also zooming in on the motives, assumptions, and beliefs driving your choices.

Cicero believed philosophical reflection was the key to unlocking self-awareness. Through it, we can transform vague feelings into clarity and random thoughts into purpose. Think of it as mental resistance training. Philosophy asks us to question, to challenge, to reframe. What drives your decisions? Who are you trying to become? Are your actions aligning with your values? By answering these, philosophy shifts our perspective. Instead of just flying through life on autopilot, we start making informed, ethical choices.

And honestly, let’s not ignore the practical perks here. Critical thinking, sparked by philosophical inquiry, helps us cut through the noise. It’s like putting on glasses when everything was blurry before. Suddenly, the world—your relationships, work, ambitions—comes into sharper focus. If you’re curious about the tangible ways philosophy connects to this idea of living well, check out this guide on using philosophy for the good life.

More than that, philosophy forces us to reckon with ourselves. It can be uncomfortable, sure. But it’s also liberating. The more I reflect on it, the more it feels like learning to hold up the flashlight in the dark corners of your mind, confronting both your triumphs and your flaws. Guilt? Desire? Fear? Philosophy doesn’t let you sweep those under the rug; instead, it asks, “What are these feelings teaching you?” And isn’t that the start of self-understanding? The start of growth?

The Dialogical Method in Cicero’s Writings

If Cicero had a signature move in his writing, it would be the dialogical method. Picture this: instead of standing on a soapbox and shouting his beliefs at the masses, Cicero spins philosophical dialogues like intricate conversations. Not in a boring, “and then this person said, and then that person replied” way, but through back-and-forth exchanges where ideas clash, merge, and evolve. It’s like philosophy as a contact sport—thought sparring.

So, why did he choose this method? For one, it reflects a deep respect for complexity. Let’s face it: life’s big questions don’t usually have neat, one-size-fits-all answers. By introducing multiple perspectives, Cicero showed that understanding isn’t about shutting people down with clever arguments. It’s about listening, questioning, and sometimes even admitting that opposing views have merit. You can see a breakdown of Cicero’s approach to philosophical dialogue in this Stanford Philosophy article.

Cicero treated the dialogical method almost like an intellectual buffet, laying out different ideas so readers could test them for themselves. For instance, one character might argue for Stoic principles, emphasizing reason and detachment. Another might advocate Epicureanism or the pursuit of simple pleasures. And through this debate—through the give and take—you get to wrestle with the arguments. Which resonates with you? Which feels lacking? Cicero wasn’t just “teaching” philosophy; he was inviting people to engage with it, to personalize it.

I find this method shockingly modern. Maybe because we live in a world where people are less interested in discussions and more into broadcasting their opinions like they’re the ultimate truth. Cicero’s dialogues remind me that true understanding doesn’t come from who shouts louder. It comes from slowing down, asking questions, and being curious—even about ideas you don’t initially agree with.

The dialogical approach also serves another important purpose: it mimics how ethical reasoning unfolds in real life. Think about the last time you faced a tough moral decision. Was it cut and dry? Probably not. More likely, it was a tug-of-war between conflicting values, priorities, and emotions. Cicero’s dialogues reflect that same complexity, that gray area where real, human dilemmas exist.

What gets me most about Cicero’s style is how it pulls you in. You’re not just reading; you’re participating. Philosophical inquiry, for him, wasn’t about reaching some final, definitive “truth.” It was a method of refining our thinking, testing our beliefs, and ultimately coming closer to the ideals that shape the good life. If that sparks your interest, I’d recommend exploring related insights on Cicero’s philosophy of dialogue.

For me, engaging with Cicero’s dialogues feels less like flipping through ancient texts and more like sitting in on a really great conversation. It’s messy, challenging, but deeply rewarding. Is that what life’s ultimate questions ask of us anyway? To wrestle, to debate, to grow? That effort seems like the common thread between Cicero’s time and ours.

Ethical Public Service: Governance and the Common Good

Cicero believed public service wasn’t just a career—it was a responsibility. He saw it as a moral calling, a duty to look beyond self-interest and work for the welfare of the community. What’s striking about his philosophy is how it’s rooted in ethical governance. Even today, these insights echo in our understanding of what it means to lead not for power but for purpose. Cicero’s principles demand us to ask the harder questions: Are our leaders focused on personal gain or the collective good? And personally, are we living in a way that contributes to something larger than ourselves?

Justice and Integrity in Leadership

For Cicero, justice wasn’t negotiable—it was the cornerstone of leadership. Without it, leaders were no better than opportunists exploiting their positions for selfish gains. A just leader, he argued, strives not for personal advantage but for fairness and equity within the community. This idea feels more urgent today than ever. You only have to turn on the news to see how failures of justice in leadership play out—broken systems, disenfranchised voices, and trust that feels irreparably shattered.

But here’s the thing: Cicero didn’t just talk about justice as an abstract idea. He linked it directly to integrity. To lead with integrity meant aligning actions with moral principles, even when it wasn’t the popular or easy thing to do. Think about this—how many modern leaders can you honestly say prioritize ethics over optics? The contrast feels stark when you compare it to the Roman statesman’s vision.

During the collapse of the Roman Republic, Cicero himself stood out as a voice of reason and moral clarity. His insistence on ethical governance—at great personal risk—wasn’t just rhetoric. It was practice. In times of political upheaval, Cicero demonstrated how leaders must hold themselves accountable to what’s right rather than what’s convenient. If you want a deeper dive into Cicero’s emphasis on morality in leadership, this piece is a fascinating read.

Justice, as Cicero saw it, extended beyond fairness. It was about creating systems where every individual—no matter their station—stood a chance at thriving. Leaders weren’t guardians of their own wealth or reputation; they were guardians of public trust. And integrity? That’s what made the difference between leadership as stewardship versus leadership as ego in disguise.

Long-Term Vision in Governance

One of the things that sets Cicero apart for me—philosophically, at least—is how much weight he placed on the future. He wasn’t interested in quick fixes or flashy solutions that only benefited the present generation. For Cicero, true leadership demanded a long-term vision. When leaders prioritize ethical decisions, they lay the groundwork for a society that won’t crumble at the first sign of challenge. That’s what he meant when he talked about governing for the common good.

Let’s zoom out for a moment. Most public figures today seem consumed with short-term wins. Elections, headlines, quarterly results. It’s like the future doesn’t exist. But Cicero asked: What kind of legacy are you really leaving behind? Are your decisions strengthening the foundation for future generations, or just barely patching cracks for now? He thought deeply about these questions, arguing that wise governance must consider the enduring welfare of the republic. His commitment to sustainability—both moral and structural—is worth reflecting on.

In his writings, Cicero emphasized that leadership wasn’t just about solving today’s problems but about imagining what today’s decisions could mean fifty, a hundred, even a thousand years down the line. It wasn’t enough to react to crises; you had to build resilience into the system itself. If you’re curious about how Cicero tied this ethic to his views on community, check out this insightful summary.

This perspective gets me thinking about how much patience true leadership demands. It’s not about rushing a project or delivering results for applause. It’s about crafting structures of fairness and opportunity that will outlive you. That’s the kind of long-term thinking Cicero championed. And if that doesn’t make you pause and reevaluate modern governance, I don’t know what will.

Cicero’s commitment to ethical decision-making wasn’t just idealism—it was practicality. He understood that societies built on shaky ethical foundations couldn’t thrive for long. Strong laws, fair treatment of citizens, and accountability weren’t optional. They were the only way to sustain the common good in a way future generations would thank, not curse, us for.

Does that feel radical to you? Or just… rare? Because to me, it feels like we’ve lost sight of what legacy actually means.

The Importance of Friendship and Human Relationships

Cicero had this almost poetic way of looking at friendship, like it wasn’t just a “nice-to-have” but one of life’s essential ingredients. When you think about it, what’s a good life if you’re living it alone? He believed that real, genuine friendships—those built on trust, mutual respect, and shared values—weren’t just comforting; they were transformative. To him, friendships weren’t about convenience or status; they were about growing together as human beings, helping each other thrive. And the more I look at my own life, the more I see how dead-on he was.

Friendship as a Source of Support and Happiness

Have you ever had that one friend who, no matter how bad your day gets, just seems to “get” you? Like, you don’t even have to explain the mess in your head—they already know. Cicero would argue that this emotional connection is at the heart of true friendship. It’s not about surface-level stuff, like grabbing coffee or tagging each other in memes (though I’ll admit, both are great). It’s about being that steady source of support and joy through all the chaos life throws at you.

Cicero wrote extensively about this in his work, Laelius de Amicitia (On Friendship). He believed that real friends make you a better person simply by being in your life. They push you to grow, to reflect, to rise above your own flaws. Think of it as iron sharpening iron—without that friction, without that give-and-take, we stagnate. And honestly? He wasn’t wrong. True friendship, the kind that doesn’t crumble under pressure, gives you the strength to face challenges without losing who you are.

He also said something fascinating: friendships based on virtue—not money, power, or convenience—are the only ones that bring deep and lasting happiness. Seems obvious, right? But when I actually apply that lens to my relationships, I realize how many of them are circumstantial, thin, transactional even. Cicero reminds me—and maybe reminds all of us—that the friendships worth holding onto are the ones rooted in authenticity and moral goodness. For a deeper dive into Cicero’s take on the emotional and moral support friendship provides, check out his profound arguments in De Amicitia here.

For Cicero, happiness and support in life are deeply interconnected with our ability to form and nurture real friendships. It’s not even just about having a safety net. It’s about knowing someone is rooting for you, someone who sees you in your rawest form and still sticks around. There’s this beautiful simplicity to his idea of friendship: it creates a kind of joy that no material success or fleeting pleasure ever could. And honestly, isn’t that the kind of peace we all want?

If you’re curious about Cicero’s broader philosophy on how emotional support through friendship contributes to well-being, I’d recommend this insightful summary here.

Shared Values and Mutual Respect in Relationships

Cicero didn’t sugarcoat it: not all relationships are worth your time. He argued that meaningful friendships can only exist between people who share the same core values. Why? Because friendship isn’t just hanging out—it’s understanding each other on a deeper level, aligning with one another’s principles and goals. Without that alignment, it’s like trying to sync two different radio stations—constant static, no harmony.

He’s especially clear on the importance of mutual respect. For Cicero, respect wasn’t just a nice bonus in relationships; it was the bedrock. He believed that when there’s genuine respect, you prioritize your friend’s well-being just as much as your own. You see them as an equal—not someone to control, fix, or save, but someone you grow with.

Let’s face it: relationships without shared values often lead to compromise. I’m not talking about the healthy give-and-take all friendships require—more like the kind of compromise that makes you second-guess yourself, lose sight of your own principles. Cicero saw this kind of mismatch as a recipe for either superficiality or eventual conflict. True friends? They challenge each other, but in a way that’s rooted in connection, not judgment. There’s this beautiful reciprocity in the friendships he describes—giving without keeping score, helping without expecting something back.

What also stands out to me about Cicero’s philosophy is how timeless it feels. Think about it: in a world full of surface-level “connections” (shoutout social media), what we crave are relationships that feel substantial, right? We want friendships where we’re heard, seen, valued. Cicero said this kind of bond is only possible when both people are virtuous—when they’re committed to something bigger than themselves. If that sounds lofty, I get it, but there’s truth here. A friendship built on shared ideals has a way of grounding you, reminding you of what really matters.

If you’d like to see more about how Cicero tied shared values to lasting relationships, this article provides some great insights here.

And then there’s mutual respect—it’s so underrated. Cicero reminded us that without respect, love fades, loyalty falters, and friendship crumbles. It’s not enough to “like” someone or even to love them; you have to respect them as an individual with their own strengths, flaws, and agency. That’s the glue that holds relationships together. Whether it’s a casual friendship or a lifelong bond, the principle holds true. As Cicero so beautifully wrote, “Friendship can only exist between good men” (and by “good men,” he meant people who embody virtue and integrity). This isn’t just about playing nice—it’s about creating space where both people can flourish.

I’ve caught myself wondering lately: how often do I look for friendships rooted in this kind of moral grounding? And, to flip the question back on myself, how often am I that kind of friend to someone else? It’s humbling to think about, but maybe that’s the whole point. Friendship, as Cicero described it, is a mirror—we see ourselves reflected back in the relationships we nurture (or neglect). And I think that’s where the real growth begins.

The Connection Between Philosophy, Politics, and Practical Living

It’s no secret that Cicero saw no distinction between the realms of philosophy, politics, and the way we go about living our day-to-day lives. For him, these weren’t separate silos—they were intertwined, feeding into and shaping one another. It’s almost like he saw life as a stool with three legs. Take away one, and everything else collapses. From political actions to personal ethics, Cicero had this unshakable belief that philosophy should lead the way, rooting everything in a strong moral compass that’s grounded in human nature itself.

Philosophical Reflection in Political Contexts

Cicero didn’t believe in abstract thinking that stayed locked up in ivory towers, disconnected from the streets. Nope, for him, philosophy was supposed to do something—especially in politics. Imagine this: you’re running a government or holding some kind of political power, and every choice you make affects thousands (if not millions) of lives. Cicero asked, wouldn’t you want your choices to be guided by the highest ethical principles?

He took the idea of philosophy and made it personal to governance. It wasn’t just, “Think big thoughts.” It was, “Use philosophy to govern wisely.” For Cicero, the ethical fabric of society was woven closely with the decisions of those in power. If leaders lacked virtue, the structure of society risked unraveling. It’s kind of wild how relevant this feels today, in a time when so many political scandals emerge because someone in power ignored their own moral compass—or didn’t even have one.

One of his most compelling arguments was that good governance requires more than just intelligence or charisma. Leaders must possess what he called consilium (or thoughtful deliberation) and align their actions with what’s just and good. It’s not enough to score political wins with clever tactics—it’s about using those wins to serve the greater moral good. You can explore more about this idea in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Cicero.

Cicero also pointed out something fascinating: moral decay in leadership causes societal decay. It’s like a rotten apple in a basket—it doesn’t just sit there ruining itself; it spoils everything it touches. That’s why he placed so much importance on tying philosophy directly to political behavior. Ethics weren’t optional. They were essential. It’s like saying, “You can’t separate the person from the leader,” which is a lesson we seem to be relearning with every passing election cycle.

And here’s the kicker—Cicero didn’t just talk the talk. He lived this balance of thinking and action during one of Rome’s most politically volatile eras. Amid conspiracies and backstabbings, he consistently leaned on philosophical principles to steer his decisions (whether or not they always worked out is another story). If you’re intrigued, the Minerva Wisdom summary of Cicero’s political philosophy digs deeper into how he underlined the importance of virtue in governance.

Ethics Grounded in Human Experience

Let’s talk about ethics. It’s easy to think of them as abstract or detached from real life, like a dusty book of “do’s” and “don’ts.” But Cicero flipped that. He believed that ethical principles weren’t just invented—they emerged naturally from human experience. It’s kind of beautiful when you think about it. Ethics, for him, were rooted not in divine edicts or arbitrary rules but in the shared realities of being human.

He wasn’t looking at human behavior from an armchair, disconnected from the struggle. He understood that to talk about what’s good or bad, you needed to look at what makes us tick—what causes joy, sorrow, trust, or betrayal. And he believed that living ethically wasn’t some idealized goal; it was tied to how we naturally seek harmony and connection. You can find a deeper breakdown of this concept in this article on Cicero’s ethical views.

Cicero argued that our moral instincts stem from a shared human nature. For example, take something as fundamental as fairness. It’s not just some abstract concept handed down to us—it comes from lived experience. Imagine being a kid and finding out your sibling got more candy than you. Immediately, you knew something felt off. Cicero would point to moments like that as proof—fairness resonates with us because it’s part of who we are.

But here’s where he took it further. He said our ethical ideas also grow out of living in communities. When we’re around other people, we naturally start thinking about what’s fair or unfair, what builds relationships versus what breaks them. Ethics weren’t just personal—they were social. And that made them even stronger. For Cicero, this was key to why ethics should guide political life as well. If our gut-level experiences tell us what’s just, wouldn’t it make sense for policies and laws to reflect that?

And get this—he believed ethical decision-making wasn’t about being perfect or always getting it right. It was about aiming for integrity in our choices, adjusting when we failed, and always circling back to what makes us whole as humans. His view on ethics feels refreshingly practical, doesn’t it? It’s not this rigid, moral high ground; it’s more of a steady compass, something grounded in our shared humanity. You can uncover more on his approach to aligning ethics with life experiences through the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

To me, this is what makes Cicero’s ideas timeless. He didn’t separate philosophy from life—he laced them together. And what came out of that combination wasn’t cold or clinical but deeply human. At its heart, Cicero’s ethics aren’t about rules—they’re about relationships, connections, and living in a way that feels true, not just to yourself but to everyone your life touches. And honestly, how can anyone live the “good life” without that?