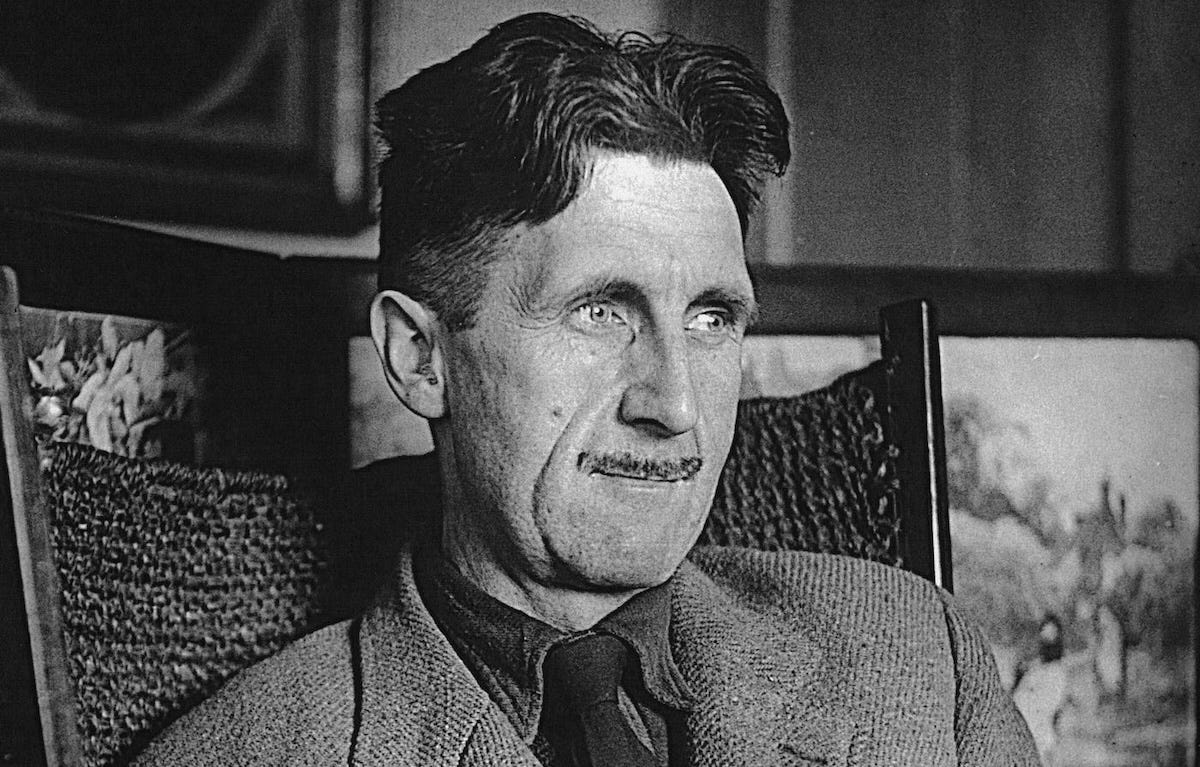

Few writers have left a legacy as sharp, unyielding, and profoundly relevant as George Orwell. Born Eric Arthur Blair, Orwell distilled the struggles of his era into narratives that resonate far beyond his time. His searing critiques of totalitarianism, embodied in masterpieces like Animal Farm and 1984, were not abstract musings but reflections of lived experience—from his time as an imperial policeman in Burma to his disillusionment during the Spanish Civil War. Yet Orwell wasn’t simply a chronicler of oppression; he was a fierce advocate for truth and justice, crafting works that challenge our complacency and call into question the fragile balance between power, freedom, and morality. In understanding Orwell, we don’t merely revisit history; we gain insight into the enduring battles of humanity, battles as relevant now as they were in his time.

Table of Contents

Early Life and Background

George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair, was a man whose early circumstances subtly foreshadowed the themes of societal observation and critique he would later famously pen. Though his upbringing may superficially seem unremarkable, it is saturated with contrasts and nuances that shaped the writer and thinker he became. Below, we explore the roots of his identity through his childhood in colonial India and the pivotal influence of his education.

Childhood in Colonial India

Eric Arthur Blair entered the world on June 25, 1903, in Motihari, a small town in British-controlled India. His father, Richard Walmesley Blair, served as a minor functionary in the Indian Civil Service, managing the British Empire’s opium trade. This colonial backdrop is no trivial detail—it informed Orwell’s early observations of class and power structures, though he would not fully grasp them until later in life. His mother, Ida Mabel Blair, moved the family to England while Eric was still a toddler, leaving his father behind to serve out his post. This separation underscored the family’s dynamic, with distant ambitions and modest means shaping their experience.

Eric’s family belonged to what Orwell often referred to as the “lower-upper-middle-class.” Financially constrained yet socially aspiring, this precarious position created a tension apparent in much of Orwell’s later work, where he dissected issues of privilege, status, and the hypocrisy of social hierarchies.

For a glimpse into Orwell’s early years and familial influences, visit the Orwell Foundation Biography, which details his family’s position and challenges on the fringes of privilege.

Education and Early Influences

Orwell’s formative years took a sharp turn when he was enrolled at St. Cyprian’s, a preparatory school in East Sussex. The school offered scholarships to children of limited means but exacted a steep emotional cost. Young Eric faced bullying, both from peers and the institution, due to his lack of wealth. These early experiences with injustice and cruelty among peers foreshadowed the acute moral lens that would sharpen over time.

Later, he attended Eton College, one of Britain’s most prestigious schools, where he mingled with the upper echelons of British society. This proximity afforded Orwell a front-row seat to upper-class behaviors, but it also stoked his disdain for an entrenched social order that rewarded birthright over merit. At Eton, Orwell developed an independent intellect, regularly publishing essays that showcased his incisive wit.

It was during these formative years that Orwell began the uncomfortable examination of his place within the systems he found so oppressive. The seeds of rebellion and his penchant for questioning authority began to take root, eventually blossoming into the striking political commentaries that defined his literary contributions.

Curious about Eton and its influence on figures like Orwell? The BBC History Page on George Orwell provides context on this pivotal educational chapter in his life.

Career Milestones: Policeman to Prolific Writer

George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair, experienced a life rich with intense contradictions and poignant observations. From his days in colonial Burma enforcing imperial rule to later living in poverty amidst the murky streets of Paris and London, Orwell’s career path offers a profound look into the making of one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. His journey—marked by occupation, reflection, and artistic commitment—not only reshaped his identity but also gave modern readers some of literature’s most enduring works.

Indian Imperial Police Service

In 1922, at the young age of 19, Orwell traded England’s damp streets for Burma’s steamy cities, eager to serve in the Indian Imperial Police. Over the next five years, stationed in various locations across British-controlled Burma (modern-day Myanmar), Orwell would see firsthand the unsavory realities of imperialism. The job required him to enforce British authority, often through coercion and violence, on a population that viewed colonial rule as an oppressive yoke. The experience etched itself deeply into Orwell’s consciousness and left him disenchanted with the empire’s moral hypocrisy.

His novel “Burmese Days” draws heavily on these experiences, painting a bleak portrait of colonial life. The book doesn’t just relay exotic scenery; it’s an indictment of exploitation, cultural desecration, and moral decay intrinsic to imperialism. Orwell’s disillusionment culminated in his resignation in 1927, as he could no longer reconcile his role as a cog in what he saw as a machine of injustice. His departure from Burma marked the starting point of a greater search: for selfhood and for truth in the written word.

For a closer examination of Orwell’s time in Burma, see George Orwell’s Time as a Policeman in British India.

The Decision to Pursue Writing

Returning to England after leaving Burma, Orwell embarked on an uncertain and challenging journey toward fulfilling his dream of becoming a writer. But as he walked away from a secure, well-paying position, Orwell didn’t step into instant success. Instead, he faced rejection after rejection from publishers, often scraping by with little to his name.

His essay “Why I Write” provides a candid introspection into his motivations, revealing a complex combination of political intent, personal expression, and a relentless need to uncover uncomfortable truths. Orwell wrote, “I write because there is some lie I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention.” These early struggles—for recognition, for purpose—convey the essence of an artist struggling to find voice and relevance in a distracting world.

Reading his essay “Why I Write” offers a vivid perspective into his mindset. You can find more insights in the Orwell Foundation’s archive.

Experiences of Poverty and Empathy

Before Orwell became the name spurring intellectual debates and literary scrutiny, Eric Blair was just one of the many invisible people struggling to subsist. Living on the fringes of Paris and London’s bustling urban sprawls, he worked in kitchens, slept in bug-infested boarding houses, and shared miseries with those society abandoned.

Orwell’s firsthand observations during this time formed the bedrock of his seminal work “Down and Out in Paris and London.” The book is not just a narrative of personal hardship; it captures systemic failures, making visible the unseen lives of society’s poorest. From the glitzy facades of Paris to London’s grimy back alleys, Orwell’s prose paints the indignities of poverty while humanizing those forced to endure it with haunting clarity.

Through these experiences, Orwell developed a profound empathy—a sensitivity he carried forward into his later works on justice and inequality. Exploring his long walks through London and his interactions with society’s most marginalized, Orwell’s transformation becomes evident. It is here, amidst the rubble of personal struggle, that we see the foundation for his later activism and storytelling.

For an in-depth look into “Down and Out in Paris and London,” this Britannica entry provides an excellent breakdown of its impact and relevance.

By navigating an unusual career path—from enforcer of imperial policy to the voice of the disenfranchised—George Orwell proved that challenges don’t define us. They sharpen the tools we need to leave our mark on the world.

Political Awakening and Advocacy

George Orwell’s profound political evolution was shaped by his first-hand experiences and unwavering moral compass. A staunch believer in justice and equality, Orwell’s journey through turbulent political landscapes served as the crucible that defined his activism and intellectual legacy. These defining moments of awakening and advocacy can be traced through his participation in the Spanish Civil War and his enduring stance against totalitarian regimes.

Involvement in the Spanish Civil War

In 1936, a bloody conflict erupted in Spain, pitting the Republicans (a coalition of leftist factions) against the fascist Nationalist forces led by Francisco Franco. For Orwell, the Spanish Civil War was not just an ideological struggle—it was a moral imperative. At great personal risk, he traveled to Spain and enlisted in the militia of the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista), a revolutionary socialist group. Orwell’s time on the frontlines, battling fascist forces near Huesca, demonstrated not only his bravery but also his conviction to live by the principles he championed in his writing.

Orwell’s reflections in his memoir, Homage to Catalonia, paint a vivid picture of trench warfare, camaraderie, and the chaotic infighting within Republican forces. A defining moment came when Orwell was shot in the neck by a sniper—a wound he barely survived. This near-death experience cemented his disdain for the petty rivalries and factionalism that plagued the anti-fascist cause. His disillusionment deepened when he witnessed Stalinist-backed factions, purported allies, turning on their revolutionary comrades, including the POUM. Orwell’s belief in socialism as an engine of equality clashed sharply with these brutal authoritarian tactics.

In Orwell’s own words, the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War lay in how “the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world.” This observation proved prophetic, as his later works grappled with the manipulation of history and truth by oppressive regimes. For more on Orwell’s role in Spain, you can explore Homage to Catalonia or this insightful article on How Spain’s Civil War Defined George Orwell Politically.

Anti-Totalitarianism and Political Philosophy

Orwell’s political philosophy was shaped by his acute observations and moral indignation at the abuses of power. Having seen the betrayals in Spain, Orwell sharpened his critique of totalitarianism, whether from the right or the left. He was unapologetically critical of both fascism and Stalinist communism, perceiving in each a common disregard for human dignity and an insatiable thirst for absolute power.

Orwell articulated these convictions with unyielding clarity in his later works, particularly in Animal Farm and 1984. These novels are more than cautionary tales—they are scalpel-sharp dissections of propaganda, censorship, and the erosion of individual freedoms under oppressive systems. Orwell famously declared, “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism.”

His advocacy for democratic socialism stemmed from a belief in balancing personal liberty with collective welfare. Unlike authoritarian models, democratic socialism, as Orwell envisioned it, was grounded in economic justice and mutual respect for civil liberties. He saw it as a pathway to eradicate poverty and reduce inequality without sacrificing freedom—a concept he explored persuasively in his essays and writings.

Orwell’s passionate defense of democratic values continues to resonate in today’s political and social discourse. To delve deeper into his anti-totalitarian stance and how it relates to his broader political views, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy on Orwell offers further insights. Likewise, his exploration of socialism is thoughtfully analyzed in Orwell’s Political Roots.

Orwell’s enduring legacy as a political thinker lies in his ability to detect and articulate the dangers of ideological extremes. Always a champion for the “ordinary” man, he warned of the creeping shadow of authoritarianism in all its forms—a warning that remains as urgent and relevant today as it was then.

Literary Legacy: Defining Works

George Orwell’s literary masterpieces carve a formidable space in the world of political commentary and social critique. His works transcend their historical contexts to become timeless reflections on power, manipulation, and the human condition. From allegorical tales to dystopian warnings, Orwell’s oeuvre unveils the mechanisms through which truth is distorted and freedom eroded.

‘Animal Farm’: A Political Allegory

Orwell’s novella Animal Farm is much more than an engaging tale about rebellious farm animals—it’s an incisive political allegory critiquing the Russian Revolution and, more broadly, totalitarian regimes. The story’s simplicity serves as a Trojan horse for profound commentary, allowing readers to uncover the dangers of concentrated power.

The characters in Animal Farm represent key figures and ideologies from the Russian Revolution. The pigs, Napoleon and Snowball, symbolize Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky, respectively, while the farm itself becomes a metaphor for the Soviet Union. Orwell meticulously crafts the animals’ descent from revolutionaries to oppressors, illustrating how noble ideals of equality are corrupted by raw ambition and the pursuit of control. The haunting mantra “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” underscores the hypocrisy and betrayal inherent in unchecked authority.

At its core, Animal Farm critiques the cyclical nature of oppression. As the animals overthrow one tyrant only to be subjugated by another, Orwell forces readers to consider whether revolutions ever truly deliver the utopias they promise. His critique of totalitarianism, particularly Stalinism, is laser-sharp, revealing how propaganda, fear, and violence sustain power.

For further exploration of Animal Farm‘s themes and symbolism, visit ThoughtCo’s summary on Animal Farm.

‘1984’: A Dystopian Masterpiece

Photo by Edward Eyer

Orwell’s 1984 is the pinnacle of dystopian literature. Set in a world ruled by an omnipresent government, the novel explores the terrifying consequences of state surveillance and absolute power. Big Brother, the enigmatic face of the regime, has become a universal symbol of authoritarianism, while the concept of “thoughtcrime” encapsulates the ultimate violation of personal liberty.

Central to Orwell’s vision is the linguistic straitjacket known as Newspeak. By narrowing vocabulary, the regime effectively limits the capacity for independent thought. Orwell understood the symbiotic relationship between language and perception; restrict the words people have, and you restrict the ideas they can conceive.

The Party’s control goes deeper than mere surveillance; it extends to rewriting history and dictating consensus reality. The slogan, “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past,” is not just a chilling reflection of totalitarian tactics but a damning indictment of the human tendency to reshape reality to serve power.

The enduring relevance of 1984 lies in its prescient warnings. In an era of mass data collection, misinformation, and invasive technologies, Orwell’s cautions resonate deeply. His novel captures not only the mechanics of tyranny but also the individual’s struggle to maintain integrity in a dehumanizing system.

To dive into Orwell’s prophetic insights, check Big Brother’s significance today.

Essays and Other Writings

Though Orwell is best known for his major works of fiction, his essays provide equally profound insights into language, politics, and society. Among these, Politics and the English Language stands out as a masterclass in critical thought and communication.

In this essay, Orwell argues that modern political language is often designed to obscure rather than clarify. He identifies how vague, pretentious, and euphemistic writing shields the truth, serving as both a symptom and an enabler of totalitarian thinking. Orwell famously declared, “Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” His observations are as sobering as they are timeless.

Orwell also delves into the use of language as a tool of oppression. By muddying reality with imprecise or jargon-heavy expressions, those in power dull public scrutiny, enabling deception to thrive unchallenged. The essay is not just a critique; it’s a guide for reclaiming clarity and truth in communication—a fight Orwell saw as vital to preserving intellectual freedom.

Outside of Politics and the English Language, Orwell’s essays like Why I Write and Shooting an Elephant reveal the intersection of his personal experiences and political beliefs. Together, they create a mosaic of thought-provoking commentary, underscoring Orwell’s unwavering commitment to illuminating the darker corners of human society.

For a deep dive into Orwell’s essay on language, you can read Interesting Literature’s analysis of Politics and the English Language.

From Animal Farm‘s ruthless allegory to 1984‘s stark dystopia and his transformative essays, Orwell’s works remain essential reading. They challenge us to question authority, protect our freedoms, and never underestimate the power of words to shape our world.

Legacy and Continued Relevance

Few authors have so profoundly shaped modern thought as George Orwell. His works, spanning novels, essays, and journalism, continue to reverberate across cultural, academic, and philosophical landscapes. Orwell wasn’t just a writer; he was a chronicler of the human condition, a critic of injustice, and a visionary who saw the enduring implications of power, language, and truth.

Cultural and Academic Impact

Photo by Markus Spiske

Orwell’s works are not merely studied—they are dissected, debated, and continuously revisited in classrooms, conferences, and cultural critiques worldwide. His allegorical novella Animal Farm and dystopian masterpiece 1984 have become fixtures in syllabi on politics, literature, and ethics, serving as touchstones for discussions on authoritarianism and propaganda. These texts explore universal fears and hopes, rendering them timeless learning experiences.

Take, for example, the ubiquitous presence of terms like “Big Brother,” “thoughtcrime,” and “doublethink.” These concepts have transcended the pages of Orwell’s novels to become part of the global lexicon, used to critique surveillance states, media manipulation, and political spin. The phrases are potent shorthand for complex ideas, a testament to Orwell’s gift for clarity and prescience.

Furthermore, his lesser-known essays and nonfiction works, such as Homage to Catalonia and Down and Out in Paris and London, are equally critical in understanding society’s hidden structures. Orwell’s commitment to exposing hypocrisy resonates particularly in academic discourse, where his works inspire researchers to explore the intersections of class, power, and morality.

For an in-depth look at Orwell’s cultural significance, visit The Guardian’s exploration of Orwell’s legacy or this article on how 1984 continues to impact cultural discussions today.

Reflection on Orwell’s Philosophy

What makes Orwell’s philosophy so enduring? At its core lies a relentless interrogation of language, freedom, and truth. Orwell believed that language was more than a tool for communication—it was a weapon, capable of both liberation and oppression depending on how it was wielded. His essay Politics and the English Language sheds light on how euphemistic and vague writing can obscure reality, making it easier for oppressive ideologies to thrive.

In today’s world, where misinformation spreads at the speed of light and phrases like “fake news” dominate headlines, Orwell’s warnings about propaganda feel eerily prophetic. His idea of “Newspeak,” the language designed to eliminate dissent by restricting thought, parallels modern concerns over echo chambers and curated narratives dominating digital platforms.

Moreover, Orwell’s meditations on freedom—both in the individual and collective sense—continue to challenge readers globally. His reflections on the nature of power, as seen in 1984, suggest that totalitarianism thrives not just through brute force but by rewriting history and distorting reality. This insight forces us to confront our own complicity in ignoring or enabling these tactics in the name of convenience or security.

To further explore how Orwell’s philosophy resonates with today’s social and political contexts, check out Orwell’s ongoing relevance or this analysis of Orwell’s philosophical insights.

Through the lens of culture, academia, and contemporary philosophy, Orwell’s legacy endures. His works challenge us not only to see the truth but to defend it—no matter how inconvenient it may be.

Conclusion

George Orwell’s life and work remain a masterclass in understanding the dynamics of power, the fragile fabric of truth, and the critical role of language in shaping human realities. Through his incisive storytelling and fearless political essays, he laid bare the ugliness of totalitarianism and stood as a lifelong advocate for fairness and honesty. Orwell didn’t merely critique the world; he held up an unflinching mirror, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and our societies.

His warnings about propaganda, censorship, and the manipulation of facts are more relevant than ever. As we wade through an era rife with information overload and questionable narratives, Orwell’s insights provide not just caution but a roadmap for vigilance. The enduring relevance of his observations is a testament to his genius—a voice unyielding in its fidelity to freedom and justice.

What does Orwell’s legacy mean to you? Let his words challenge your perspectives and inspire action, inviting us all to write our own narratives with courage, clarity, and conscience. Through Orwell’s lens, the fight for truth is not just a battle—it’s the very essence of what it means to be human.